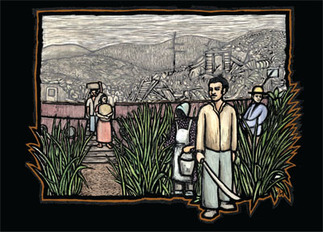

Fritz Muller Fritz Muller My hosts at the small cabin I found on airbnb, a friendly couple from Wisconsin, describe what surrounds their hand built, octagonal retreat as “jungle.” It’s a Hollywood word, full of Tarzanic imagery, an exoticizing word that conjures up fantasies of white colonial explorers cutting paths through the homelands of tropical people. I gently explain that this is not a jungle. It’s second growth subtropical forest, taking back land cleared over a century ago during the rise of the coffee kingdoms, a richly dense ecosystem, full of tree ferns and hanging vines, but not the primordial rainforest they imagine. Many of the tallest trees are imports, brought here to shade the coffee: red blossomed tulipán from West Africa, pomarosa and guamá from Venezuela. In the reclaiming of those cafetales, the monte, the wild, begins with yagrumos, shooting up from the million seeds each tree can produce, armed by its symbiosis with the little Azteca ants, who defend the saplings from insects and choking vines in exchange for shelter and the food provided by special glands yagrumo has evolved for the purpose, so called mullerian glands, named for pioneering German naturalist Fritz Müller, who, dismayed by the failed revolutions of 1848, went off to be a naturalist in Brazil.  Ausubo Trunk Ausubo Trunk Yagrumo always seems to me to be a talkative tree, waving its white palms in the air, announcing by flipping its palms back and forth like a child playing a tossing game, that the rain has begun to fall on the far slope, that a fresh breeze is blowing in from the Mona Passage, that the first edges an announced hurricane, the frothy skirts of Guabancex, her terrible winds and heavy downpours curving their way clockwise across the Caribbean, are approaching. Yagrumo is resilient. It bends its soft wood, and what breaks quickly regenerates. Not like the ancient hardwoods who take decades to reach maturity, ausubo, guayacán, capá blanco and capá prieto. (I say who because they are beings to me, family ancestors with stories to their names.)  San Ciriaco migrants in Hawai'i. www.rlmartstudio.com San Ciriaco migrants in Hawai'i. www.rlmartstudio.com After Hurricane Hugo, I was taken into the Luquillo rainforest by a biologist friend of my father’s. Whole hillsides looked like New England in November, leaves burnt brown by the salt wind, and ranks of tall mahoganies reduced to piles of splinters. This isn’t the disaster it seems to the uninitiated. The forests of my island evolved in a realm of storms, and ned the cleansing breaths of an occasional uprooting the way the western forests of North America need fire. But for the human inhabitants it’s another story. Don Luis, my best friend’s 97 year old father, still remembers finding a piece of zinc roofing impaling a large tree in a deep valley after the cataclysmic San Felipe hurricane of 1928. He and other elders have told me how when they crept out of their shelters it was to an unrecognizable landscape, stripped bare of all vegetation. In 1899, hurricane San Ciriaco left 100,000 homeless and starving. Don Luis’ father told him about the lines of silent, hungry people walking toward the coast, to “las emigraciones,” not knowing where in the world the ships were taking them except that it was away from eating leaves and mud. Over five thousand of them ended up in the cane fields of Hawaii and streets of San Francisco. I interviewed a remote cousin of Don Luis, a third generation Hawai’ian Puerto Rican whose family never returned.  Don Luis can name all of the dozens of hurricanes to strike the Western cordillera since then, and the near misses whose paths arced northward to the east or west of us, Hugo which tore pieces out of cement buildings on the island municipality of Vieques and left Indiera untouched, and Georges, which uprooted half the pines on our land and it was ten years, he tells me, before the mediopesos nested there again. I can imagine these slopes, a few years after San Felipe did its worst, greened over by the pioneering masses of fern and shrub and the graceful silhouettes of young yagrumos, hands raised to the sky, ants scurrying up and down the slender trunks, repelling the attempts of bejucos to get find a smothering foothold, spreading their shade for the delicate flowers of alegría to repopulate the scoured hills with color.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed