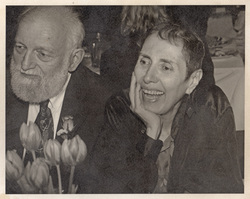

1960, Puerto Rico March 2, 2011 A few days after my last post I found out that my mother decided to stop treatment for multiple myeloma and start hospice. Sometime between a few months and a year or so, my mother will die, and I'll no longer be able to call her on the phone to share the joyful news that Paraguayan campesinas are marching with signs saying "Without Feminism, There Is No Socialism," and declaring that the best way to end climate change, hunger and extreme poverty is a feminist land reform that puts agriculture into the hands of women, or tell her about the delicious new word I discovered, or the wild thing I saw on wing or furred foot or scaled belly, or read her the newest bit of draft writing. I've dreaded this moment all my life, since I first understood that someday my parents would die.  c. 1970, Chicago Over a period of days we made plans for everyone to visit my mother within the next two months, then, as her illness seemed to suddenly escalate, changed that to weeks and finally days. Ten days ago I flew to Boston and by the time I arrived, my mother was no longer able to hold a conversation. March 15: My mother's laughter is a thread running through all my memories, along with her sharp insights, her one foot in front of the other courage, her delight in colors, birds, textures, plants and rare words like finifugal--"of or pertaining to the shunning of endings." Soon I'll be writing much more about her, but for now I'm concentrating on breathing, crying and scanning photos. March 21: True to herself as always, my mother refuses to use Depends, refuses to be lifted, and through sheer force of will, rises to her feet to sit on a commode. Her will, it seems, holds the atoms of her being together, waiting, we think, til the last of the grandchildren arrive--not because she wants to see us, but because she knows we want to see her, and she can't stop taking care of us, can't check us off her list yet. Tomorrow, when we're all here, we tell her her tasks are done. Her decline has been dizzyingly fast. I find myself wanting to talk to the mother I've been chatting with on the phone with once or twice a week for an hour at a time, to tell her what it's like, her dying. To say Mami, you were amazing today, or to laugh with her about the fact that when she's asked if she wants water, or a cover, or anything else, she's been saying "not particularly." Last week's mother would enjoy hearing that about herself. Or how she shifts into Spanish, in a high, childlike voice. She'd be so interested. So my plan is to write to her, talk to her, keep conversing--because today's mama, deep inside herself, tells me to shut up and go away when I explain that the trip to the bathroom is no longer possible, tells my father to make me stop. I'm glad she had her commode victory. Meanwhile, stevia sweetened coconut milk chocolate pudding, abundant good food, lots of talking to each other and messages from friends gets us through. Plus rescue remedy. Gonna try for some sleep. March 22 In the middle of the night last night I was up with my mother for several hours, adjusting medication, helping her onto a commode. Today she mostly slept, and hasn't been speaking, Sometimes she waves her hand around, lifts her arms, but mostly she sleeps, breathing through moisture accumulating in her throat, and we speak to her, letting her know both that her work is done, and that her legacy continues. It's been a joy fighting for her wishes, in the face of a nurse pushing catheterization, or those who want to over medicate. At one moment last night I was telling someone that we aren't going to decide what's best for her or interpret signals--we'll ask until she says (she was still saying things then) and she said softly "uh huh." Old friends came by to sit with her and the last of the grandchildren arrived. We also talked a lot about funerals and burials and have decided to dispense with funeral home services. I'll wash her body with my daughter & niece, we'll dress & wrap her, and we're going tomorrow to see a place that makes burial baskets, fiber containers, and all sorts of biodegradable boxes. I'm exhausted from being up til 5 am, so off to sleep shortly.  1986, Cambridge March 23: My mother Rosario died at 3:30 a.am yesterday, March 23rd. I had gone to bed at midnight. I woke sudden;y at 2:40 with an image of her still face, so I got up and went upstairs. She was breathing heavily, as she had been for the last day. Lunece, her favorite caretaker for the last three years, had asked to do a night shift, even though she works two jobs and has children. My mother had asked her to be around as much as possible. She and I sat and talked for half an hour or so, and I spoke to my mother a little, as I'd been doing all along, telling her we were all OK and she could go. One of the hospice nurses had told us that women like her, who have been driving forces in their families, also have a strong identity in caring for their kin, so we should also tell her her legacy was safe with us, that she'd continue. So I told her we were OK because of her, that we were still following her instructions, that my father was napping and drinking enough water. I decided to go back to bed. Five minutes later I heard Lunece come down. She woke my father and told us Mami had stopped breathing. We went upstairs while my niece Olivia called everyone to come over. My mother took three or four more breaths at long intervals and then stopped. We all stood around, talking, crying, laughing. After a while, everyone else left the room and my daughter, my niece and I washed my mother's body and sang to her, first a sacred song from the Yoruba tradition, and then Canta y No Llores, one of her favorite songs. We dressed her in a long red dress she loved, and arranged her on her bed. We decided not to use a funeral home at all, and to do things ourselves. Yesterday we went to an alternative burials company called Mourning Dove, to look at biodegradable caskets. They had burial baskets, paper maché cases, cardboard coffins and then suddenly we saw a beautiful casket of woven fibers in several shades of brown. When we asked about it the owner told us it was made of banana leaves. We all gasped. It was perfect. She also showed us a breathtakingly beautiful shroud made of brilliant golden yellow dupioni silk, lined with little packets of white sage sewn into the lining. My mother wanted to be allowed to decompose, to become soil and plants. Most cemeteries don't allow that, but we've found a way. Although the place she'll be buried requires cement grave liners with lids, we can request that it be put in upside down, without the lid, like the top of a butter dish, so her casket rests directly on soil. We can't plant things over her, but she'll be able to join the earth as she wanted. We're also putting soil from our land in Puerto Rico and Vermont into the casket with her. I'll be staying here another week, then flying home to be part of the Sins Invalid show and taking care of various things. Then I'll come back and stay with my father for a few weeks and help him reshape the house for this next phase of his life.  This afternoon I went out to buy a dress for the burial. My mother loved bright colors and dressing in beautifully constructed garments and I had only packed jeans and shirts. I found the perfect dress, soft plummy red material, beautifully cut to flatter, and some short boots with lace insets. When I came back to the house, for a few seconds I thought my mother was sitting upstairs in her well lighted room and I was all set to run up and show it to her, knowing she'd get as much pleasure from it as I did. For those few seconds I forgot she was dead, so that remembering was like falling down an elevator shaft. All day people have been stopping by. Sometimes it nourishes me and sometimes I have to get away and be quiet. Sometimes I cry spontaneously. But any connection with someone who's lost their mother recently makes me sob. I called my friend Shannon and was sobbing before she picked up the phone. I met my mother's friend Denny in the street in front of the house, and we embraced and sobbed right there. I make huge batches of sugar free, dairy free chocolate pudding for my father. Ice cream and chips disappear fast. Puerto Rican rum on chocolate mousse ice cream. Thai noodles. Baked organic chicken thighs. Delicious Chinese food brought by a friend. Death and food. And stories. All kinds of stories. Mostly my father telling about his own life to the grandchildren who live far away. Tales of all the years doing tropical island ecology among the sharks and the flying fish and Moray eels. Stories of his early political life, of how he and my mother became communist farmers in rural Puerto Rico. Upstairs, my mother's body, laid out on the hospital bed, becomes less and less like her. I no longer want to go into the room. I want her in the earth, embraced by microorganisms, become humus. My beautiful mother needs to become soil and ivory bone, needs to break down the web of her tissues into usable bits of protein, needs to convert herself into beetles and earthworms and spores and be eaten by birds who will chatter and swoop among the trees of Mt. Auburn cemetery, her last craft project--to unravel. Tomorrow she can begin.

5 Comments

|

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed