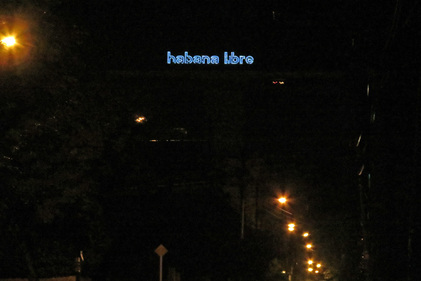

View from my friend's top floor patio. View from my friend's top floor patio. Returning to the United States from Cuba always feels like time travel to me. I've been to a different century, and when I come back and try to explain my experiences to people, to tell them what I saw, how I interacted with the people of another time, no one understands or believes me. The fragments of the story may register: no ads on tv or on the streets, universal health care, free higher education, but what they mean in people's lives, what they add up to, what it feels like to take that for granted, doesn't. And without the visceral understanding of what Cubans have gained, there's no truthful context for the hardships, the mistakes, the struggles of daily life.  Then there's the huge wall of misinformation I have to penetrate. Every time I go, someone asks me if the Cubans will let me return, still envisioning some 1950s Hollywood version of a tropical gulag. Won't they grab you? they ask. (I explain that while many Cubans have hugged me, I've never been grabbed, except by US Immigration officers when we came back via Miami. We were detained for two hours while they questioned me about what I did in Cuba, and examined every piece of paper in our bags.) There's the receptionist at my old stroke rehab facility, who, when I came back from Cuba in 2009, walking, instead of in my wheelchair, told me in a lowered voice that Cuba had the highest suicide rate in the world because no one there has access to healthcare. On the contrary, everyone has access to healthcare, they export doctors to countries in need, and the highest suicide rates are in the formerly socialist countries of Eastern Europe. Even well informed people assume Cubans feel hostile to people from the US. In all the years I've been traveling to Cuba, I've never met anything but warmth and generosity from Cubans, who, unlike many people in the US, know how to distinguish between government policies and the people of a country.  Duty free Cancun Duty free Cancun As I wrote nearly five years ago, the first jolt on return is how pervasive consumerism is. As you pass through security in Cancún on the way to US flights, you are welcomed to virtual US territory in the form of a vast array of duty free items in shining glass cases, spotlit from above--so many that it's a kind of maze you have to get through. It's a temple to consumption: alcohol, perfume, jewelry, designer clothing, electronics. Exhausting, overstimulating, meant to provoke artificial appetites. Then we get on the plane, with so much more leg room than Cubana's flight, and a crew crew that's so much less helpful. I thumb through my individual copy of the Sky Mall catalogue, full of objects designed to meet nonexistent needs at great expense, like, I kid you not, a fake, miniature back yard for your dog, with two square yards of fenced Astroturf and a pink, scented fire hydrant. Also straps to keep your bed from getting mussed up while you sleep, little waterproof lights to make your shower water turn colors, and a life sized "realistic" yeti lawn ornament that costs over two thousand dollars.  But the biggest jolt is loneliness. The loneliness of living in a society where so many people pursue their paths alone, don't know their neighbors, don't know who they can count on, can't remember that our struggles are shared, and spend themselves on getting through the day. In Cuba there is plenty of hardship. There are many basic goods that are either impossible or exhausting to get hold of, life is logistically wearying, and bureaucracies can be stifling and arbitrary, but there is still a deep sense of being in it together, of looking out for one another. Social development, including the greatest gains of the revolution, outstripped economic development, and it's caused serious problems, but that social development also gives people some of the resilience they need to cope with the dire consequences of 52 years of a cruel US trade embargo, and of internal errors that come at least in part from the siege mentality that the blockade and ongoing attacks on Cuba have generated.  In Cuba everyone argues, gets in your business, gives you unsolicited advice, help, affection. It's not a place where you could die alone and not be found for weeks. It always makes me laugh when people imagine that Cubans don't dare complain about the things that are wrong. Complaining is practically the Cuban national sport. Everyone wants to tell us what they think about the recent changes, the endless making do off the shortages, what's getting better, what's getting worse, who left for the US or Europe or Latin America, and increasingly, who's coming back, as other economies crumble without the safety net of socialism.  Pretty soon I'll post more pictures and tell more stories, talk about the Cuban feminists and artists and medical professionals and patients I spoke with, about beloved Havana itself, and the projects I intend to take on. But right now I have to tell you that far more than I miss the heat of the sun, the sound of Spanish, or the endless supply of fried plantain, I miss that intimacy that comes from being, with whatever criticisms and frustrations, part of a great social experiment, the attempt to build a society based on sharing what there is, taking care of one another, not allowing the corporate bandits that are ransacking the world to set foot on their shores. I miss the sound of Cuban voices arguing, bartering, flirting, laughing, debating, finagling, exclaiming, teasing, complaining, speculating, recommending, insisting, blessing, questioning, sighing, singing, being lavishly affectionate and getting all UP in my business.

1 Comment

Gloria

3/13/2014 10:56:32 am

Thank you so much for this wonderful post. Reading your piece has taken me back to Cuba. Most of the things you talk about, very much resonate with my own experience in Cuba-last summer. I miss the people the most, and I am disappointed at how fast I have taken up my usual fast-pace life-style in the U.S. after coming back from Cuba. Your post really brought back some of the warm feelings I had while I was in Cuba--feelings that are hard for me to replicate in the U.S.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed