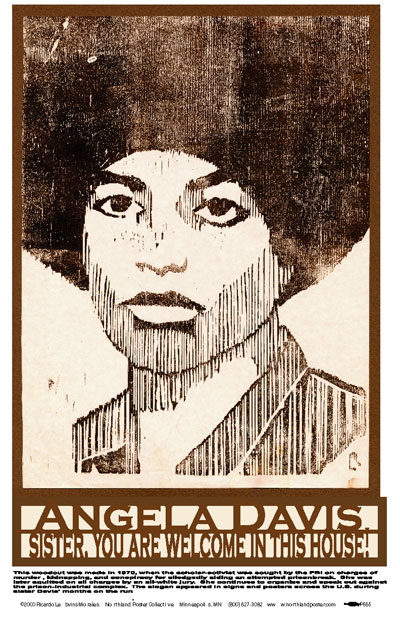

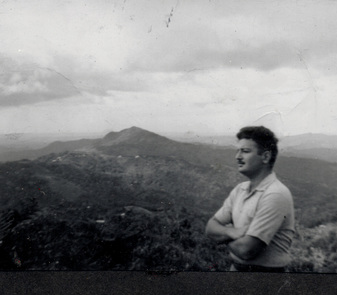

Poster by Ricardo Levins Morales Poster by Ricardo Levins Morales For those who don’t know, right after the election, someone proposed wearing safety pins to indicate that we are allies to anyone being attacked in the post-election upsurge of hate crimes, and while many embraced it, many also criticized it as superficial, and debate over this tactic continues to rage. There are several things that this very heated argument ignores. Many People of Color rightly critique the possibility that white liberals will wear a pin as a form of self-soothing, feeling brave for taking a largely symbolic action, without actually doing the necessary work of building ally muscle. But it seems many assume that these are the only people who would consider wearing a safety pin as a statement of intent, that anyone wearing one is doing nothing else. It’s an assumption based in fury and frustration, and utterly understandable but inaccurate. Seasoned and dedicated allies also have reasons to wear them. I have been a lifelong radical for whom expressions of solidarity are as natural as breath. I am old enough to remember the window signs we put up when Angela Davis was in hiding that said “Sister, you are welcome in this house.” Of course, she wasn’t going to knock on our door just because of a sign, and we didn’t expect her to. We were speaking to each other and to the state, affirming our commitments, and making a public statement of alliance. It was one small part of the organizing work we were doing in support of Black Liberation, and it mattered. Symbolic actions have power to inspire, to build connection, to express an idea that moves people forward. Secondly, four highly targeted people in my life have told me that seeing the pins on people’s clothing makes them feel safer and lifts their spirits, and that’s enough of a reason for me. But I think the most important point being missed is that in times like these, we need each of us to take a step forward from wherever we are. People are scared, angry, and feeling urgent, wanting our allies to have already arrived where we need them to be, and ready to be scathing towards those who are not. I am not suggesting that anyone be less angry. Rage is appropriate. But no matter how impatient they make us, directing our rage at potential allies who are taking their first baby steps is the wrong target.  My father, c 1952. My father, c 1952. In 1954, following the Puerto Rican Nationalist attack on the US congress, there were massive roundups of radicals in Puerto Rico, and my communist father was among the arrested. When the police came for him, and our neighbors gathered to watch, Gregorio Pla, a liberal agronomist friend of my parents with whom my father had been organizing an agricultural cooperative of small scale coffee farmers, stepped forward and shook my father’s hand. It’s an act of courage and integrity that still moves me to tears. He wasn’t a communist. He wasn’t a target of the repression being unleashed on our island. His action didn’t prevent my father’s arrest. But he stepped up. He said, “I am with this man, even though it may put my name on a list, even though the political police are here and watching me, even though all the neighbors, some of whom are informants, will remember this. I stand by him.” There are people who will respond to the empowerment of the far right by shifting the direction of our whole lives toward a different or more dedicated kind of political work; people who have a lifelong practice and will keep doing what we already know how to do, people who will wake up to the intensity of oppression we had an abstract sense of but were shielded from the day to day trauma of; people who believe this is a democracy, that Democrats are our champions, are still holding tightly to illusions that liberation is achieved by voting, but who feel cheated, outraged, shaken, on whom it is dawning that we don’t all live in the same country; people who are gripped with terror of the violence and political repression already unfolding and bound to escalate, wrestling with panic, and thinking about emergency responses, local networks, preparation; and people who have never done a single public political act, for whom putting on a safety pin is an act of courage and integrity, like Gregorio’s handshake, people who are stepping out of privacy, invisibility, complacency. I’ve listened to a lot of stories about how people are radicalized, and it’s never a result of being railed at. People change because of personal engagement with human beings whose lives are different from their own, because events reach a tipping point beyond which they can’t respect themselves if they don’t speak out or act, because the story they’ve been living by is disrupted, because they are able to connect their own struggles with someone else’s. So my question about the symbolic action of wearing safety pins is how can we deepen its significance and turn it into a doorway through which people can grow? Are there more impactful actions we can attach to it? Can we create safety pin trainings on how to actually intervene in a hate crime? How can we teach people about both the power and flimsiness of sanctuaries and safe houses, the history of successful and unsuccessful efforts of allies to support and get the backs of the most targeted—everything from the Underground Railroad to Danes wearing yellow stars to the Central America sanctuary movement. The thing is, we all start from the places our histories have brought us to, and we all have the opportunity, always, to grow, connect, be bigger in our solidarity, clarity and capacity to make change. Every step forward matters, and this moment of upheaval is a great time to encourage everyone around us, wherever they are on the spectrum, to take the next one, and then the one after that. Support Aurora’s work here: https://www.patreon.com/auroralevinsmorales

Join Aurora’s mailing list here: http://www.auroralevinsmorales.com/mailing-list.html

2 Comments

11/20/2016 03:22:23 pm

As always Aurora you encourage the best in me. Thank you. I am very grateful for your presence in this world.

Reply

Ariana

11/28/2016 05:21:05 pm

Thank you for this thoughtful and nuanced perspective. It's informing my conversations with others, and I particularly appreciate the encouragement to think about other symbols in past resistance movements.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed