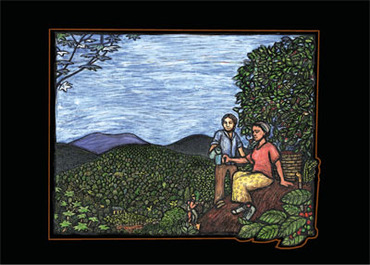

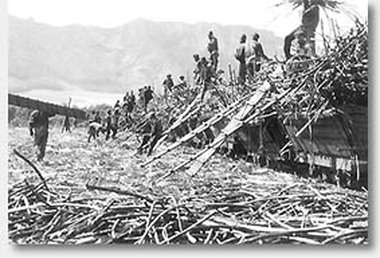

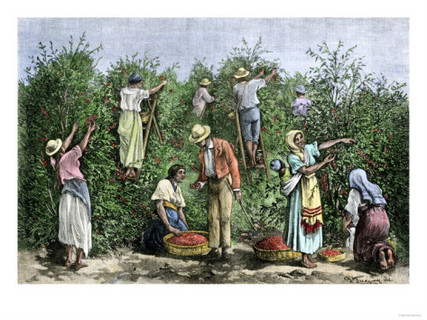

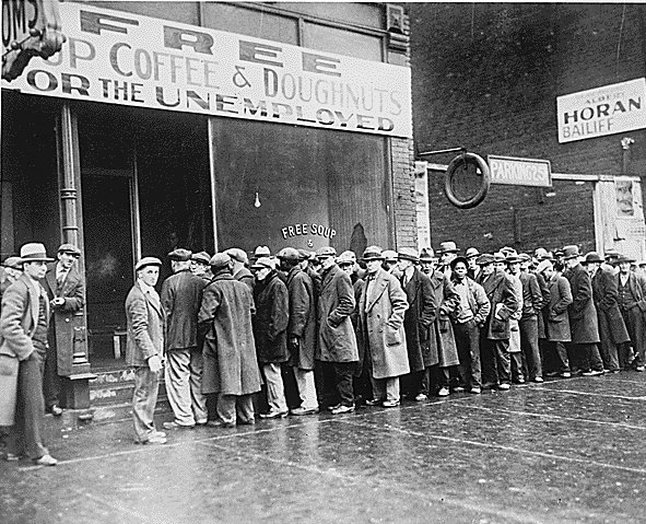

I am the descendant of Taíno people whose tropical ecosystem allowed them to put in minimal work and reap abundant crops of carbohydrates, who could spend a modest amount of hours fishing and gathering shellfish, and have plenty of time to develop sophisticated art forms and elaborate rituals. Their culture honored artists and trees, created breathtaking carvings in wood and shell, invented hammocks knotted from the fiber of maguey, polished rings of stone, ceramic pots and figures elaborately worked with earthen dyes, and days long festivals of poetry and song. I am also the descendant of the Spanish colonizers who came and slaughtered, tortured, raped and enslaved them; who came fresh from the famine-ridden lands of Europe, from rocky soil and harsh drought, and created a moral universe of harsh and virtuous labor to match. Before they kidnapped, tortured, raped and enslaved my African ancestors into the sugar fields of the Caribbean, they did their best to seize the labor of the indigenous people of the islands and turn it to generating profit, which they believed in with frenzied devotion. You can feel the hot outrage rising from page where a conquistador reported that "neither threat of punishment nor promise of reward" could induce my Taíno people to work more than they had to for their survival. As yet untrammeled by avarice and ambition, I imagine them looking at each other, and back at the red faced intruder with his odd ideas, and responding with one voice, "Duh!"  A few weeks ago my brother, Ricardo Levins Morales, posted his weekly blog on Opine Season, revealing his quiet rejection of sugar as a part of his diet, built on an earlier decision to stop drinking alcohol, and let slip that coffee is still a daily ritual for him. For me it was the other way around. Coffee was the first to go, and given my epilepsy and shattered adrenal function, that may have saved my life. I grew up in a landscape entirely restructured to serve three great addictions of modern life: sugar, tobacco and coffee. The sugar grown on our coastal lands, sucking nutrients from the soil and leaving it impoverished, was also converted into a fourth, rum.  I was born and raised at the boundary between the townships of Yauco and Maricao, in the very heart of coffee country. The smell of the roasting beans and woodsmoke still fills my heart with joy and longing. Everyone I knew drank a last cafecito before bed, and so saturated was the blood in their veins, their metabolisms so conditioned to the stimulation of those Ethiopian berries, that they slept like babies. (Oh yes, the babies had cafe con leche in their bottles.)  My mother wouldn't go that far. We didn't start drinking coffee until grade school, and as best I recall, only on special occasions, with a spoonful of sugar, and dollop of cream cheese turning deliciously beige and cheesecakey. I was born into a series of early traumas that predispose me to jitters and adrenal overreaction, and once I started independently consuming coffee, I very soon discovered that it made me tremble for hours and feel slightly sick, with that nauseated sensation you get after a sudden jolt of adrenaline. My body dished out the misery too soon for me to experience it as aftereffect. It turned out to be the same with alcohol. For a few years I drank wine with my friends, and the occasional shot of Puerto Rican rum in Coke or coconut milk. But by the time I went to college, very small amounts would make the room spin, and I started passing out from half a glass of beer, so except for a glass of champagne when Nixon resigned, I stopped.  My mother was a quiet but constant alcoholic, sipping sherry and vermouth, Barrilito rum and Gordon's gin, Benedictine and Brandy, Kahlua and Grand Marnier. Alcoholism ran in her family, and I'm fairly certain the genetic variation which makes ethanol overwhelm my brain in seconds, and which has only recently become something you can be tested for, comes to me from her lineage. I wonder if it was the hard drinking Spaniards, the cohoba snorting Tainos, or the palm wine imbibers of West Africa who bequeathed it to us, or whether it sprang into being from the confluence of those wildly disparate lives, violently clashing between the creak of the trapiche, extracting the juice from the stalk, and the thud of the barrels being loaded into ships' holds to play their part in the triangle trade.  Although sugar wines have been fermented since ancient times, particularly in the South Asian lands where the sweet grass originated, rum was first distilled in the Caribbean, by enslaved Africans experimenting with molasses, and then white slaveholders concentrating the alcohol until it burned. Dulce caña me provoca, wrote Cuban national poet Nicolás Guillén, con su jugo azucarado, el cual despues de probado, siempre es amargo en la boca. "Sweet cane provokes me with its sugared juice, which, after it's tasted, always turns bitter in the mouth." And he continued, "to cut the cane is my fate, but destiny is so cruel that when I wound it with my blade, it receives all the good, for from my blows, it lives, while I die from its blood." Addiction, like Christianity, came to the islands on the point of a sword, to the sound of shackles and whips.  The second crop was tobacco, wrested from its sacred place, promoted and commercialized into a necessary accessory of the good life, from the poor man's chaw through carved pipes and hand rolled cigars, to the delicate pinch of snuff from an elegantly enameled box. Tobacco covered part of the Morales family acreage, along with pasture for cattle and most likely some citrus, root vegetables, and maybe a patch of rice. They lived in the low hills of the northeast, along the Toa River, but my mother's aunt and uncle didn't die of lung cancer. It was liver failure.  Where my immediate family lived, in the heights of the cordillera, the cycles of coffee set the rhythms of people's lives. During the harvest, children went to the hillsides, not school. As teens, they courted to the gardenia scent of white coffee blossom, with its bewitching powers, and girls washed their faces in the petals to make themselves lovelier. Adults in their hard working prime filled baskets, then sacks, then trucks, then warehouses with the red and green berries, raked the fermenting fruit til it fell from the pale seed within, husked, roasted, ground and brewed it in their homes, and then celebrated the end of the harvest in wild festivals. Old women bent over metal cans of black beans and burnt sugar warned their descendants that the smoke could wither them.  In the famine years of the thirties, it was sometimes the only nourishment. Black coffee and a rind of green banana. Like Bolivian coca, it kept hungry people going, through otherwise unbearable overwork and deprivation. It still does. Every morning, millions of people get up and drink their coffee in order to meet the demands of capitalism on their tired bodies. Without it, they can't push past the exhaustion of the unreasonable work day, work week, work decade. Without coffee, we might have to notice how unreasonable those demands actually are. We might have to stop in the middle of sirens, deadlines, bells, conveyer belts, ringing phones, and take a nap.  I'm lucky. While my nostrils still flare with pleasure at the smell, and the other night I dreamed I was eating coffee ice cream, my body refuses to let me drink it. There's no struggle, for me. Retribution is instantaneous, so it isn't willpower or virtue. That door is just closed to me. But imagine if we all stopped revving our battered engines, if we could feel our tiredness beneath the pulse of caffeine, and give it its due. If we defended our bodies' limits instead of violating them. Imagine if neither threat of punishment, nor promise of reward could make us work harder than we have to. Lying in the hammock on a still evening, talking around the slow fire, what might we dream up then?

8 Comments

Alison Ehara-Brown

5/21/2013 03:47:40 am

Aurora, gracias por compartir con nosotros. Powerful, clear, and inspiring you are, as always, querida. Lovely to share this road of love and liberation with you. Konnoronkwah (Mohawk: I to you -- the most precious medicine -- love)... Ali

Reply

Aurora Levins Morales

6/28/2013 03:21:10 pm

Thank you, Lucy!

Reply

Caridad Souza

6/30/2013 12:04:36 pm

Aurora, como siempre, this was lovely. I just got Kindling and will look into getting you to do a webinar with CSU. Enjoy today. Love, Cari

Reply

Aurora Levins Morales

6/30/2013 01:21:18 pm

Cari! How great to hear from you. I'd love to virtually visit CSU. Abrazos, A.

Reply

Owen T.

9/23/2013 03:21:18 am

I saw you read this at La Peña last night. I love it and expect to share it with my fellow radical coffee drinkers for years to come. I particularly like the connection with the Tainos' refusal to work constantly. European peasants fought that same fight when industrialization arrived in the 19th c.

Reply

Aurora Levins Morales

9/23/2013 05:19:09 am

Yes, I've treasured that conquistador quote since I first read it-- the total incomprehension of the Spaniard faced with Taino work lives, and the obvious and devastating consequences of that culture class. Coffee breaks at work were actually created by corporate bosses, to keep workers energized through the long day.

Reply

10/5/2013 05:44:51 am

I am printing this out and clipping it into my copy of "Kindling," so that when I share the book with people this piece will be part of it! Thank you for writing it.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed