|

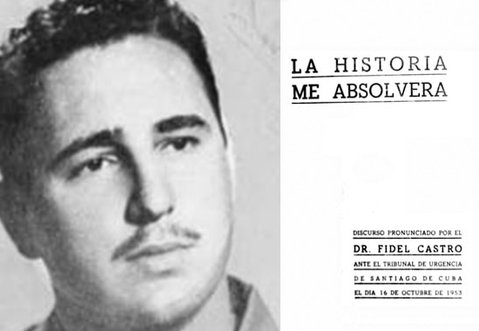

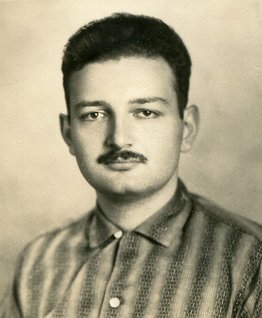

One of my favorite songwriters, Cuban Pablo Milanes, wrote: Lo que brilla con luz propia, nadie la puede apagar, su brillo puede alcanzar la oscuridad de otras costas. What shines with its own light, no one can extinguish, its brilliance reaches the darkness of other shores. I was born on one of those other shores, in what a few weeks ago, one Cuban revolutionary described as “grey times.”  I never saw Havana in those years. I only knew by rumor that it was a playground for the rich and corrupt, run by the US mob and the CIA, a place where children begged in the streets and shined the shoes of foreigners for a bite of bread, where Black Cubans couldn’t go in the front doors of night clubs that served up their music to white Cubans and foreign tourists. My friends who were children then remember the tortured bodies of union organizers, student activists, anyone who dared to protest, dumped late at night in the quiet streets of the suburbs, remember their terror of the police. Across Latin America, dictatorships flourished, and even the most basic striving, for enough to eat, for a roof overhead, were met with gunfire, disappearance, beatings, people dragged into jail cells buried so far from sight no one ever saw them again. When I was young, these stories floated above my head, spoken among adults who met in our living room, between my parents. The names of overthrown presidents, assassinated leaders and massacres hung in the air, while anti-colonial movements erupted and were suppressed, erupted and were suppressed. Young Cubans rose up to take the Moncada barracks and were killed, tortured, exiled and a young lawyer promised that history would absolve him. A handful of small victories and a litany of defeats, of broken branches piled high, waiting for a spark. I was born in early 1954, in a tiny, homemade hospital built by pacifists, in the western mountains of Puerto Rico. In those coffee region barrios, children grew up hungry and parasite infested, without running water or indoor bathrooms, their parents couldn’t read, wages were abysmally low, and young men were being drafted to die in Korea and then Viet Nam for an empire that stole our natural resources, exported our unemployed to the slums of US cities, and conducted horrible experiments on our bodies without bothering to let us know.  Carlos Raquel Rivera, Marea Alta, 1954, linoleum, Collection Museum of History, Anthropology and Art, University of Puerto Rico Carlos Raquel Rivera, Marea Alta, 1954, linoleum, Collection Museum of History, Anthropology and Art, University of Puerto Rico I was two when an overloaded cabin cruiser called the Granma carried 82 revolutionaries from Mexico to the south coast of Cuba, and almost five when the guerrilla movement they ignited and the urban insurgency of workers and students brought down the Batista dictatorship and ended US control of Cuba. They sang: se acabo la diversion, llegó el comandante y mandó a parar. The party’s over. The comandante came and said stop, and a tidal wave of hope swept through Latin America and the Caribbean, raising surf as far as Africa, and across Asia, all the way to the Pacific’s western rim, igniting some of that piled up tinder. Within weeks, new revolutionary parties and movements sprang up all over Latin America like the little purple day lilies that shoot up after it rains. By May, Cuba’s first law of agrarian reform went into effect and large plantations were seized and distributed to campesinos. Like the Haitian Revolution before it the Cuban Revolution changed the definition of the possible, and the grey and bloodstained social landscape of the Americas began to show some color.  Richard Levins, 1957 police file photo. Richard Levins, 1957 police file photo. It was the year the CIA, on behalf of United Fruit, overthrew the government of Jacobo Arbenz for daring to commit agrarian reform and defend the right of workers to organize into unions. It was the year four Puerto Rican nationalists fired shots in the US House of Representatives, where congress was busy telling the United Nations that our suffering and lack of sovereignty was an internal matter and none of their business. In the roundups that followed, my father was arrested, and then released and my parents had papers made out for my adoption by pacifist friends if anything happened to them. I grew up among the children of poor coffee laborers, their bellies swollen with malnutrition and worms, for whom meat was mostly a seasoning for starch, whose water had to be fetched by hand in buckets from often distant springs, while at the nearby hospital old men on benches spat blood from tubercular lungs. But just over the horizon a million Cubans, including 100,000 children, fanned out into the countryside and taught their elders to read and write, wiping out illiteracy in a year. Country clubs and mansions were becoming schools, and all of sudden everyone had access to food, education, medicine, and the arts. Nicolás Guillén, home from exile wrote, I Juan with nothing, yesterday with nothing, and today with everything. If we got up early, when the first light was just spilling across the coffee farms of the cordillera, and the CIA jamming station hadn’t kicked in yet, we could listen to Radio Havana reporting on how many acres of land were in the hands of the poor, how many fields planted with food instead of cash crops, how many children had fresh milk, the diseases eliminated, infant mortality falling and life expectancy rising, all those mundane numbers that added up to a hurricane of change, to landslides and uprooted fences and the first unfurling leaves of a new society built for the benefit of its own people. I have sang Guillén, what I had to have. Between our mountain farm and closest edge of Cuba was an island of pain, was Papa Doc and Trujillo, armed thugs and torture cells, secrets and whispers and underground organizing. Between us, Juan Bosch was elected and overthrown and US planes flew over our farm to make sure he didn’t come back. One day in 1964, my father came back from his weekly trip to the university where he taught, with a letter that made my mother light up and clap her hands. It invited my father to come to Cuba to help reshape the University of Havana’s Department of Biology into an incubator of revolutionary science. My brother and I were packed off to one colleague and two sets of grandparents for a month, and my parents flew off, by way of Prague, to see the brave experiment for themselves. Four years later, we all went together, and I got to walk the streets of Havana for the first time, and breathe a different air, filled with enthusiastic struggles, laughter, and hard work. It was 1968, the year of the Tet offensive, of King murdered in Memphis and cities on fire, Red May in France, the Chicago Democratic convention, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the Tlatelolco massacre of students in Mexico City. I was fourteen, and people my age were drilling in the streets to protect their country from the next Bay of Pigs, were veterans of the literacy campaigns, studying ways to build a country. We rode around Havana on buses, lined up for ice cream at Copelia, listened to vigorous discussions of public policy and international affairs, and met Boris, a 19 year old who took us under his wing and took us seriously, probed our ideas and encouraged us to see ourselves not just as children of revolutionaries, but revolutionaries in our own right. I read Granma and discovered a whole world of people trying to build human lives in places that never showed up in the US media except as hot spots, flaring into public view for a few seconds.  Aurora , 1971 Aurora , 1971 In Cuba, adults asked me what I thought Johnson would do next in Viet Nam, about the potential of the Black Panthers, and movement discussions about the strategies of non-violence vs. armed self-defense. It was a country full of people who knew they were in it together and rejoiced. When we returned to Chicago, where we lived at the time, a city under the rule of Mayor Richard Daly and his violent and corrupt police force, Cuba had spoiled me for the tedium, pointless regulations, and punishments of high school. That inextinguishable shared sense of purpose that shines so powerfully had blazed up inside me. Within two years I had a radio show, a box of poems and had left school to take part in the social movements of my time. I felt like a time traveler returning from the future with news from a less barbaric age. Each time I travel to Cuba, some large piece of my life shifts on my return. I become unable to tolerate something that had become normalized. My standards go up and I rebel. I demand more from my life. Cuba is a bright spark of navigation in my sky.

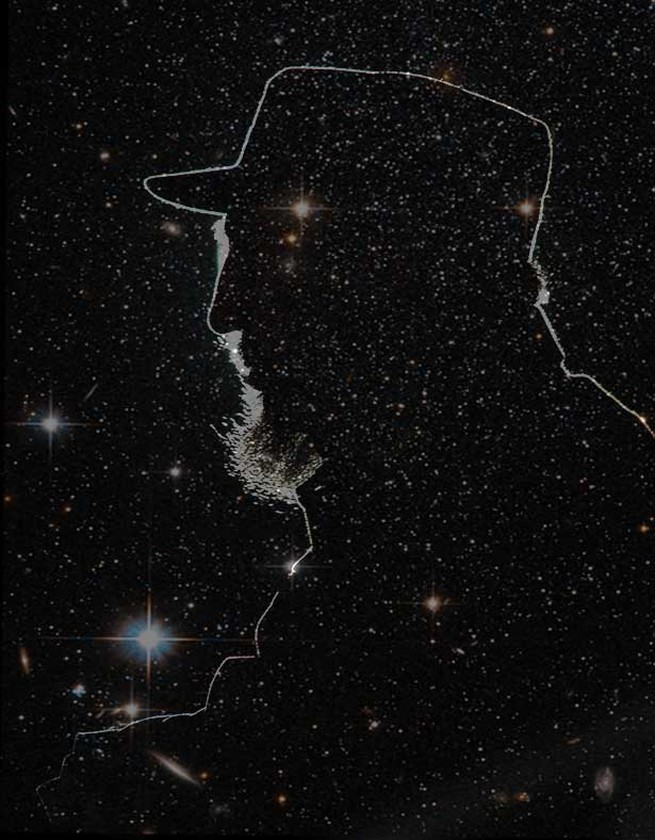

The next lines in Pablo’s song are Bolivar launched a star, that shone next to Martí, Fidel exalted it to travel through these lands. Pundits will argue about Fidel forever, weighing up facts and rumors, influences and mistakes, braiding and unbraiding his personal story from the story of his people and the revolution they made together, but for me, a Latin American Caribbean child growing up in the deep shadow of US empire, Fidel was a man who sowed stars across my continent, a whole milky way of constellations that still burn above our grim times, pointing the way toward a different future, in which each one of us shines with our own light, and together, we are as bright as the sun.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed