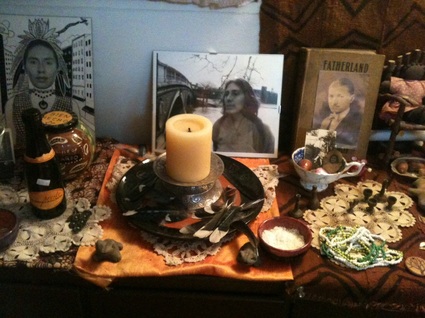

Becky, Debra Shultz and Me at gender seminar, c.1994 Becky, Debra Shultz and Me at gender seminar, c.1994 I first met Becky Logan in February, 1993, at a five day residential graduate school seminar in Washington, D.C., called The Worker and Her Writing. It was led by writer and activist Minnie Bruce Pratt and Pat Murphy, a vocational rehabilitation counselor with expertise on questions of women and money, work and violence. In my evaluation, I wrote "This seminar was probably the best formal learning experience I have ever had. It was purposefully and thoughtfully designed to create an atmosphere in which profoundly meaningful conversations could take place about our work as women... It was deeply empowering and I formed relationships I expect will last for many years."  Unknown No Longer, Virginia Historical Society Unknown No Longer, Virginia Historical Society The meaningful conversation I began with Becky that winter lasted twenty years, mostly over the phone, and ranged over a vast terrain of shared curiosity and outrage, scholarship and ritual, and all the complexity of being who we both have been in the world. If ever an alliance met the original definition of radical, ours did--two passionate intellects digging for the roots of things in order to change them. While she sifted through land deeds and household inventories, tracking the class positions of all the participants in Virginia witch trials, I scratched and scrabbled in the footnotes of colonial histories of the Caribbean, searching for missing women. While she went beyond Tituba to find the stories of African American victims of witchcraft persecutions, I copied the names of Africans and Jews condemned by the Caribbean branch of theInquisition, and children buried in the dead season of the sugar cane cycle, when hunger and damp combined to lay them low. But also we dug for the roots of our own lives, of our parenting, of our wounds and our growing.  Becky was the one I took my historical puzzles to, or the glorious tidbits, the unlikely connections. Really! I hear her say, her tone intensely interested. Fascinating! Together, we worked from our different angles to turn genealogy into familial social history, pushing past who, where, and when, into how and why. What a gift it is to delight in the same things! My mother and I had that, and so did me and Becky. Delectable turns of phrase, metaphors crafted into spells, well written mysteries, the finding of evidence for what we knew was true.  Doxil charm for Becky, showing soil bacteria from Italy. Doxil charm for Becky, showing soil bacteria from Italy. To say she reminded me of my mother, that when my mother died and could no longer answer the phone, I thought "Becky will pick up some of those conversations," this is high praise. I would get the tug, the urge to call her, and it would be the right moment, when she'd just been thinking of something she wanted to tell me, when something had happened, when a shift was taking place. I had that tug the day she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and happened to be one of the first to call after she knew. And having listened and talked my mother through the final three and half years of multiple myeloma, I knew how to be with her, how to be present with her mortality, how to research the poetry of her chemo drugs, find out what they were made of, to help her befriend them: platinum, yew trees, red earth bacteria. I can hear her voice now, as I did just a few days ago, saying "That's an excellent question." I had just asked her what it was like to be her that day, drifting toward death in the hospice ward of Seattle's Swedish Hospital. Tired as she was, she had field notes to share: the varied reactions of doctors and nurses to the fact of her dying, the rush of visitors, and the satisfactions of time with family. She'd emailed to say she wanted to talk, knowing I would understand the project, the quiet time she needed for it, how busy she was with the slow withdrawal from her flesh.  My egun (ancestor) altar. My egun (ancestor) altar. I got the tug just now, and called the hospital room. Her partner, Ruth, answered the phone and said it was perfect that I'd called. Becky had died fifteen minutes before, just as I was getting a glass of water, finding the phone number, plumping the pillow for comfort, preparing to call. She went easily, Ruth said. I was raised by atheist parents, communists, scientists, materialists in the Marxist sense of the word, but when it comes to questions of spirits and the afterlife, my roots are among the country people of Puerto Rico, and the land itself, saturated with lives, filled with stories. The people I grew up among talked to the dead all the time, were visited in dreams, saw the traces of those who had lived before them everywhere in the landscape. It isn't a New Age thing with me. It's very old ages. It's Taino ghosts nibbling guavas in the branches, Yoruba egungun sharing food and rum over a household altar, the people I've always seen from the corners of my eyes, the images in my inner eye when I touch their belongings. And once or twice they've pushed books from shelves that fall open before me with the exact information I needed for my research.  Like Becky, I'm a revolutionary witch, politically materialist and alive with magic. For me, the roots of things include our beloved dead, not as memories or metaphors, but as part of the fabric of the world. My conversations with my mother are more muted now. I must listen harder to hear her answers, and in the state in which she now exists, many of my day to day concerns have become vague for her, part of a physical realm that has faded. But sometimes she flashes into focus, and once, I felt her take my hand, and then place her palm on the middle of my back. So I'm expecting to hear from Becky, in that elusive, less literal way that the dead have of visiting, which doesn't stop me from sobbing as I type, for the real life, out loud, right there on the phone conversations we won't get to have, the books I'll write and be unable to send to her, the questions that will go unanswered. Dearest Becky, I will have to write to you in the air, with candlelight and a finger dipped in water, to ask, now that you dwell with the ancestors, can you look something up for me? Can you send me new friends to talk with? Because the friendship of women has always been my most enduring and resilient of lifelines, far more so than my marriages and romances, and now one of the most important friends of my adulthood has gone on to become something else. "May your journey be easy, gentle, astonishing," I wrote to her in my final letter, just days before she died, "and may whatever comes next turn out to be joyous, and really, really interesting." Fare well, my dear.

1 Comment

seeley

8/12/2013 04:08:58 pm

thank you for sharing this. i'm feeling her passing, and your reflections mean a lot.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed