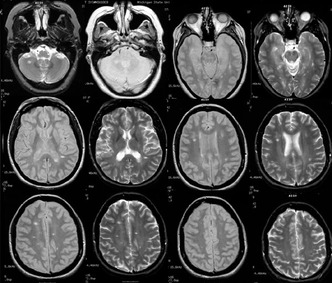

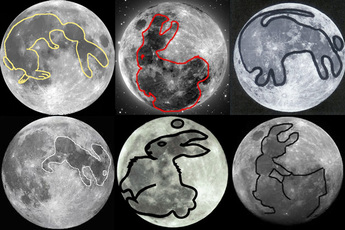

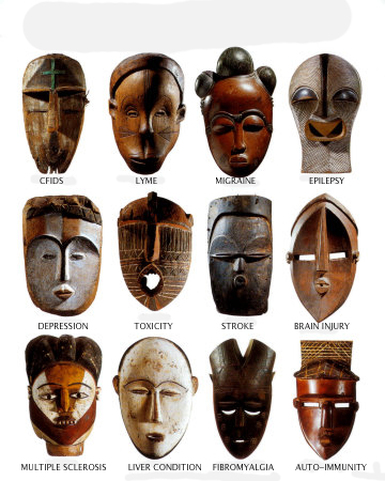

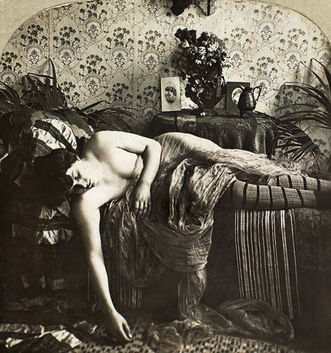

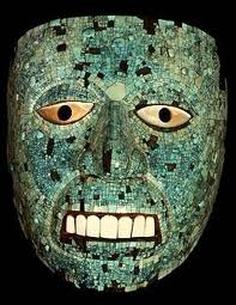

Living with my father, for the first time I am managing my health in full view of a family member. Until she moved out at eighteen, my daughter lived with my chronic illness and the series of catastrophic crises it routinely generates. She had to navigate the choppy seas of a childhood full of emergencies and the vast doldrums of my exhaustion, inevitably more of a caretaker than she should have had to be.  In that world of impending shipwrecks, avoiding the tips of icebergs was enough to handle. The deep, cold, roots of my condition, the massive flanks and fissures, were places I went alone, in the dark, filling notebooks in sleepless nights of poring over self- help books and websites and list-serves organized by shared and overlapping diagnoses, drafting new protocols,(liver cleansing, chelation, alkilinity, rotation diets, EMF shielding) looking for explanations, or at least relief, consulting one narrowly focused healer after another, trying out the pills, potions and practices that resonated, tracking changes (seizures, menstrual cycles, sleep and appetite and pain,mood swings, dreams, the clarity of my mind,) traveling by sonar. The people by my bedside saw the cups of bitter tea and bowls of pills, but not the insomniac research behind them.  Wild Stream Orchid I am living with my father for the first time since I was sixteen. Not since the full-impact years of single motherhood have I had this much responsibility for another person's well-being, and I'm drowning, unable to balance his needs and my own, both of us in shock at our changed worlds since my mother died and I uprooted myself to come here. I am struggling to exercise self care, which is hard enough without this balancing act, hard enough when no one's watching up close, seeing each choice I make. For decades I have studied my body and its responses, learned what helps and what doesn't. I have encyclopedic knowledge of the effects of nutrients, herbs, externally applied substances and internal energy practices, am adept at adding micrograms of this and that to the scales, balancing pain relief with a need for alertness, the adrenal boost and the sleeping potion. Tonight I introduce him to the plants we both take as bedtime tinctures, show him pictures of longstanding allies, the companions I've turned to in pain-wracked nights and sleepless pre-dawns. The purple bells of skullcap, periwinkle stars of vervain, maroon and yellow blossom of wild stream orchid.  I tell him that last night I was drenched in sweat. Do I know why? he asks. I explain that I live at the hub of multiple diagnoses, where symptoms criss-cross and can be claimed by any of a handful of causes. Night sweats can be Bartonella or Babesia, two of the co-infections of Lyme, or CFIDS, that uncharted sea of devastating neuro-immune dysfunction that some people still insist is hysteria. Adrenal stress alone can drench the sheets. We've just watched an episode of The West Wing in which President Bartlett has an MS attack. The First Lady wipes down his damp brow, says gently that he's sweated through his clothes, and the Surgeon General explains to the gathered staff that tiring himself could lead to spasms of his legs. Suddenly my eyes fill with tears. The severity of my illness has been dawning on me in a new way, again. I, too, sweat through my clothes, wake up in damp sheets, and for the last two years, the muscles of my calves and feet have gone into frequent, excruciating spasm. I don't know much about MS, what the relationship is between demyelination and sweat, but my own MRIs show a multitude of "punctate areas of high signal intensity" in the white matter of my brain. Maybe it's the scars in the white matter that are making me sweat.  The constellations of lesions in my brain are interpreted differently by each specialist who looks at them. Like astronomers from different cultures, they impose their own meanings, seeing different pictures in the patterns of light and dark, the Dipper or the Great Bear, Lyra or Weaving Girl, a rabbit or an old man in the stains of shadow on the moon. Those splotches revealed by magnetic resonance have been explained to me as degenerative vascular disease, multiple sclerosis, the scars of dozens of seizures, the tracks of Lyme or Bartonella or both, the wreckage left by hundreds of complicated migraine episodes constricting blood flow, or whatever it is that allows CFIDS to damage the brain. Like the classic fable of the blind men and the elephant, no one can offer me a complete picture.  But in the highly politicized, profit driven worlds of the medical industry and the labyrinths of publicly funded social services, which of the overlapping diagnoses I pursue, and in what order, and in whose view, may ultimately be a strategic, rather than a medical decision. The symptoms may be the same, but it's easier to get resources under some identities than others. After thirty years of advocacy and research, it may be better, at least officially, to have CFIDS than chronic Lyme, a diagnosis that has lost physicians their licenses in some states, and is at the center of a raging war for profit, power and prestige. So, late into my insomniac night, I revisit CFIDS after a few years of doing my suffering under other names. What strikes me is the accumulation, in recent years, of solid evidence not only that CFIDS is a physical, measurable illness, but also documenting its severity. After decades of ridicule and dismissal, it's been less exhausting to downplay the intensity of how sick I feel, then to deal with the emotional battering of people's skepticism, the assumption that this is attention seeking melodrama, the endless unsolicited recommendations of everything from chamomile tea to affirmations. But I think the worst of it is my inability to tell the truth of what I experience without feeling like every word must be a gross exaggeration, when in fact it's usually a serious understatement.  In a 2010 speech, leading CFIDS researcher Dr. Anthony Komaroff cites a major study on the severity of CFIDS, using a research survey called the SF-36, considered one of the best tools for measuring how sick people are. When compared to subjects with heart failure and depression, CFIDS patients had a physical status similar to heart failure patients, the highest levels of pain and lowest levels of vitality and social functioning of all three groups, and substantially better mental health than the depressed patients. Another study looked for physiological evidence of the wiped out feeling known as "post-exertional malaise," comparing levels of molecules that detect pain and fatigue in CFIDS patients and healthy controls. For the healthy subjects, the levels peak eight hours after exercising, at two and half times the pre-exercise level. For those with CFIDS, the levels continue to climb until they are nine times higher than normal, and they stay that way up to 48 hours after exercising. These are only two among many studies cited, and reading them is like suddenly discovering that I've been granted citizenship, and can come out of hiding. I feel vindicated, like a crime victim whose testimony is finally believed. And then, browsing through the introduction to Peggy Munson's groundbreaking anthology Stricken, I find this: "Dr. Mark Loveless, an infectious disease specialist, proclaimed that a CFIDS patient 'feels every day significantly the same as an AIDS patient feels two months before death.'"  I have a dear friend who is facing a second bout of ovarian cancer, an exquisite being whose honesty and vulnerability, courage and humor, affect me like the most potent of my medicinal tinctures, an essence of integrity. When she writes, I write back, even when I'm very ill. This week I wrote to her about the words "terminal" and "interminable" side by side, about life-threatening and life-draining as categories of illness. When my mother was in her last several years of living with multiple myeloma, she would call me for advice on how to live with such exhaustion, how to cope with such limited energy, such restricted capacity, and I would tell her how I do it. I held her hand while she passed through the territory I live in, and on out of life. Now I live in the room she died in, and I'm still exhausted.  Although people with CFIDS, Environmental Illness and similar conditions have a high rate of suicide, and epileptics are six times more likely to be seriously depressed than healthy people, I am fully committed to being alive. But there's an intensity of suffering for millions of us, that most people have no idea of, and the crazy-making result of its invisibility is that at the same time that I'm struggling to tender my body and soul the very best loving care I can, silently affirming my capacity to heal, all the while that I'm trying to live as fully and joyously as I can within these states of exhausted pain-- in order to protect myself from complete collapse, in order to get access to even minimal support and ridiculously inadequate care, I have write on form after form, chant loudly and continuously to agencies and authorities, acquaintances, family and friends: I'm sick, I'm sick, I'm sick.  Me at 18. Photo by David G. White I have another dear friend whose body instantly declares her disability to the world, who must fight to be seen as competent, while I fight to be seen as needing help. Within the ever-shifting dynamics of capacity and incapacity, illness and health, vulnerability and strength, each of us holds truths that are partly submerged. I know my survival depends on communicating both my competence and incompetence, my resilience and know-how, and my stark limitations; that I have to hold my own and surrender, accept limits and push against them. So this is what I'm thinking about these days, days that fall away from the clock, when I sleep from dawn to noon, or, like today, from midnight to 5 am. How to be publicly sick and empowered. How to bring my whole self into view and still be safe, supported. How to be sick and undiagnosed and unashamed; or over-diagnosed, in a storm of contradictory instructions and stories, and stay calm, accepting uncertainty. How to shed the the million ways I am named by others and just be. How to wear my own face.

14 Comments

Aurora,

Reply

Randy

1/7/2012 01:00:19 am

You said it as well as it can be said, sister cous’! Thank you! Another brilliant blog.

Reply

Natasha

1/7/2012 01:55:36 am

I love your beautiful illustrations and images. Keep on keepin' on.

Reply

Sasha

1/7/2012 02:36:13 am

Aurora, this piece shimmers with truth and beauty. Your writing and illustrations transmute the most unimaginable suffering into something luminous and strikingly brilliant. I wish you moments of rest and peace in the midst of your life's most difficult challenges. Sending love.

Reply

Amber

1/8/2012 05:33:26 am

Wow.

Reply

Barbara Cohen

1/19/2012 03:17:06 am

Aurora; reading this made me cry. Having a chronic disease myself, but one not as debilitating as yours, makes me ache for you and the situation you are in. I send you images of fullness--that life is full--full of pain and full of beauty, full of joy and full of hopelessness. May your days be made lighter by knowing that you have touched many of us with your beautiful words.

Reply

Kimberly

2/23/2012 07:42:20 am

Beautiful Aurora, so eloquently said. I bow to you to your courage, strength, tenacity, gifts of the soul & body. I am grateful to have come this way.

Reply

billie rain

6/25/2012 07:53:13 am

thanks again, aurora. a wonderful article.

Reply

amber

6/25/2012 09:42:29 am

this piece is simply stunning, aurora. your words kiss the page, weave the stories of our experiences with both truth and heartbreaking beauty. <3

Reply

HI Aurora. Thanks so much for this. It's one of the inspirations for a blog that I just started-- mostly because I'm excited about bringing together a good list of other blogs and links (like this piece of yours)-- and hoping that the broader activist/left community reads/contributes. With much appreciation and respect...

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed