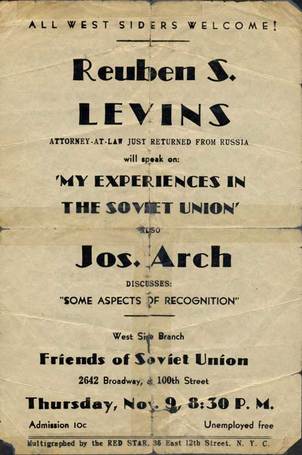

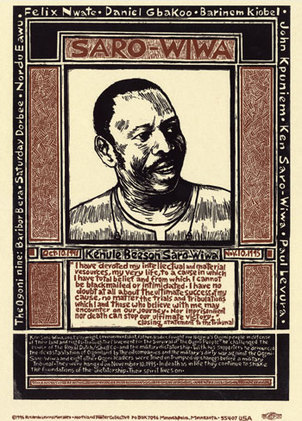

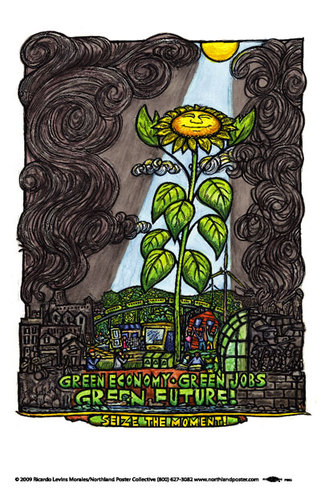

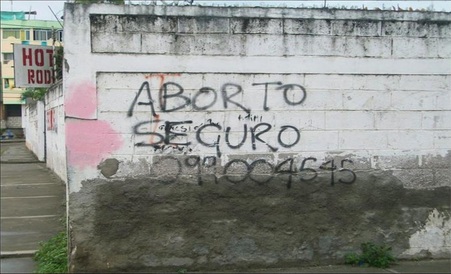

Picket in support of lunch counter sit in. My first picket line, age 4. Picket in support of lunch counter sit in. My first picket line, age 4. One of the advantages of growing up in a multi-generation radical family is the way history inhabits our bones. During the last century, my family has openly defied the oppressive policies of the Russian Tsar, the Spanish crown, the U.S. government, the colonial government of Puerto Rico, the House Un-American Activities Committee, the FBI, and the Chicago police; resisted the US invasion of Puerto Rico, union busting, segregation, evictions, sexism, classism and racism in higher education, and police brutality; organized garment workers, unemployed women, rural coffee workers, hospital workers, women's consciousness raising groups, rebel radio shows, art collectives, radical theater groups, Jewish peace activists, tenant strikes and antiwar teach ins, for access to birth control and the right to unionize; agitated on behalf of the wrongly imprisoned, the exiled and the assassinated in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, from the Scottsboro Boys to Cece MacDonald, from Sacco and Vanzetti to Archbishop Romero, the Chicago Eight to the Cuban Five; supported people struggling to build just societies in Cuba, Viet Nam, Chile, Mozambique, Nicaragua, South Africa, and everywhere else, and opposed wars in Europe, Southeast Asia, Central America, the Persian Gulf, Southern Africa and the Middle East. We have inherited a broad, visceral experience of radicalism.  My grandfather Reuben, 1933. My grandfather Reuben, 1933. We've inherited decisions about coalitions and splits, arguments about priorities, urgencies and long views, strategies that worked and didn't, choices that backfired, and those that bore fruit. Our cousin Evaristo Izcoa Díaz started one banned newspaper after another, and died young from tuberculosis he contracted in prison. He was outspoken and provocative, good on some issues, bad on others, defended a mulata girl raped by the sons of the town's elite, and denounced the behavior of US occupation soldiers, but badmouthed Afro-Puerto Rican bomba dancing as "savage." My great grandmother Leah organized immigrant women in sweatshops and worked with Margaret Sanger, distributing birth control information in the tenements; and the support of Sanger and many otherwise progressive people for eugenics contributed to the Nazi ideology that exterminated Leah's village in the Ukraine. We inherited my grandfather's leadership of the Communist Youth League when it split from the Young People's Socialist League over opposition to WWI, the complex relations between the Communist and Nationalist parties during the repressive fifties in Puerto Rico, the struggles of second wave feminism to grapple with multiple, seemingly contradictory layers of privilege and pain, the life-eroding concessions of labor, and the undisciplined fury of rebels measuring militancy in decibels. The thing is, we inherited lessons, context, big pictures, and big pictures is what this blog post is about.  Coal-fired power plant, Huaibei, China Coal-fired power plant, Huaibei, China Counterintuitive as it is to people facing decades of losses, it remains harder to organize for small gains than big ones, and trying to solve one problem at a time almost always leads to betrayals and mistakes. Take the compact fluorescent bulb...please. The supposedly green choice for illumination uses less electricity to light up your days and nights than incandescent ones. That's the only problem it was designed to address, and we're encouraged to think that by buying them, we contribute to a greener, more sustainable world. But compact fluorescent bulbs are packed with toxic mercury that affects both producers and consumers. The work of making them has been outsourced to Chinese factories run on dirty coal, putting US workers out of work and Chinese workers in danger. And once made, they must be shipped from China to the US on freighters fueled by oil. The problem is that lowering our electrical consumption is too small a goal.  Ken Saro-Wiwa by Ricardo Levins Morales Ken Saro-Wiwa by Ricardo Levins Morales What we really need is a way to produce energy that is ecologically and socially clean--no coal, no oil, no union busting, no black lung and mercury poisoning, no devastated communities and poisoned landscapes. In order to achieve that, in spite of the immense resources of greedy oil companies with the power to overthrow governments and repress labor movements, we need many more people passionately committed to the task. But once we let go of the illusion that we can save the planet by making small consumer choices and leaving the greater structures intact, once we reach for the stars, we have way more power to inspire each other. Once we think big, the indigenous people of Amazonian Ecuador and the residents of Richmond, California can join forces with the heirs to murdered Nigerian environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa to fight back against Chevron together. Once we think big, innovators in technology and participatory democracy will collaborate. When we think big, hope is no longer deferred. Our small steps add up to a journey. We stop thinking that limiting our scope increases our chances. We don't throw anyone overboard for the sake of a little gain. When we think big, we fight for everyone.  Green Jobs by Ricardo Levins Morales Green Jobs by Ricardo Levins Morales In fact, anytime what we're fighting for brings us into conflict with the legitimate needs of another group of people, it's a sure sign that the picture is too small. There is no inherent conflict between the preservation of forests and the employment of loggers. We just need to devise a sustainable form of forestry, and an economy that is built to sustain people and trees with equal care. True, it's a much bigger job, but it's a lot more interesting, and has a much better chance of working than letting us be pitted against each other. La Coyuntura  There's a word in Spanish that was part of all the leftist speeches of my youth: coyuntura. It means the situation, the circumstances, the current historical moment. If the big picture is a constellation of stars by which we plot our course, the coyuntura is the muddy ground we stand in while we stargaze. The bloody, difficult present. In the coyuntura, we have not yet won. Each act carries risks we must weight. Not all our alliances will hold. Repression can escalate, alongside bribery. Some of what we want to build can't yet be done. We point ourselves toward those dreams, but the conditions don't yet exist to make them happen. Standing there in the mud, our job is to keep talking about stars while we shovel slush, add gravel, pass around hot thermoses. Sometimes that means supporting solutions that are painfully inadequate, that cost us, but still move us toward the the universally humane future we long for.  Ecuador: "Safe abortion" and a phone number. Ecuador: "Safe abortion" and a phone number. Since my teens I have fought for women's right to abortion. I do believe that life begins at conception. I do believe that aborted fetuses die real and significant deaths. But here in the coyuntura, I believe the reproductive sovereignty of women is an essential foundation of the world I'm building. All of us, those who support abortion and those who oppose it, should be demanding the development of safe, free, 100% effective birth control. Parenting should be well paid, well supported work, so that no woman aborts because motherhood will bankrupt her and smother every other dream. And until we achieve it, I choose the sovereignty and safety of women who are pregnant against their wishes or best interests, over the brief, precious lives of those barely formed seedlings. When Rafael Correa, President of Ecuador, says he'll resign sooner than legalize abortion, he is refusing to recognize that when we can't yet have it all, we must choose the path that most expands our capacity to get it all in the future.  After several years of trying to implement a bold new plan, the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, by which rich countries would pay Ecuador half the value of the oil under a priceless stretch of rainforest in exchange for leaving it there, and raising less than what was need to pull it off, President Correa was forced to accept that the national economy required drilling for some of that oil to pay for the social programs they are committed to. They are doing so very carefully, in the way that causes the least damage, for the sake of a nation of empowered, ecologically minded citizens. Supporting Ecuadorian women's right to abortion is actually the least damaging path toward protecting Ecuadorian children. Empowered, sovereign, with control over their reproductive lives, Ecuadorian women can fight for effective birth control, social support for the work of childrearing, and the rights of mothers, and make abortion unnecessary.  But big pictures, and strategic grappling with the coyuntura, essential as they are, aren't enough. In spite of the revolutionary bravado I also inherited, injustice is traumatic. It does real damage to our bodies, our relationships, our emotions and intellects. We're all trying our best, hampered by millenia of PTSD. In order to stay true to our biggest visions, and stay accurate in our day to day assessments of our next steps, we need to heal, actively, consciously, continuously. We need to keep inventing and honing the practices that allow us to understand what has happened to us, and keep making medicine. We need to acquire a toolkit for facing and recovering from the trauma of ongoing oppression as we work and weep and imagine and love our way out of it. What's In Your Medicine Bag?  My personal medicine bag has been gathered over a lifetime of activism. Here are the main ingredients:

A thousand years from now

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed