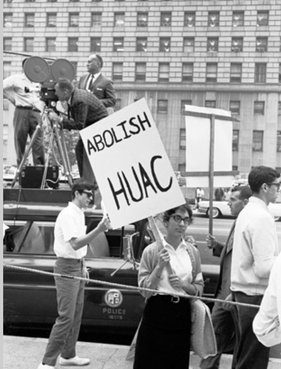

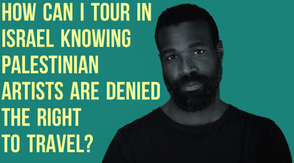

I vividly remember the day, in 1959, when my father was called up before the House Unamerican Activities Committee, during their hearings on the Puerto Rican left, of which he was a part. My parents had been blacklisted since 1951, when, on graduating from Cornell University, it was made clear to my father, a member of the Communist Party, that he would not find a job. Facing the possibility that he would be drafted into the army to fight in the newly erupted Korean War, my parents decided to go to Puerto Rico, unsure whether my father’s refusal to fight would result in jail time and separation. In Puerto Rico, a neighbor of my mother’s aunt pulled my father aside, told him she was part of a cell of the Nationalist Party, and that the FBI was visiting each place he applied for work, warning them not to hire him. On the advice of Alabama communist Jane Speed, who had moved to Puerto Rico in the late 1930s, they bought land, so they would at least have food to eat. In 1956 they moved back to New York so my father could attend graduate school at Columbia while my mother took classes at City College and parented me and my brother Ricardo. On that day in 1959, my mother sat on her bed beside the phone, waiting tensely to find out what would happen to my father. I was five, old enough to feel the weight of the threat. As it turned out, when they asked him, "are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party," my father refused to answer based on his Fifth Amendment rights, and when the panel continued to question him, walked out, and because it was 1959 and not 1953, nothing happened to him. By 1961 he’d become employable again, and got a job at the University of Puerto Rico, and although we continued to be visited regularly and were under surveillance, though our neighbors were questioned about our habits, our visitors, and the possibility that our shortwave radio, used mostly to listen to the BBC, was really for communicating with Soviet submarines, unlike many others, we didn’t suffer any major consequences. But when my father called, that day, after he had walked out, and the journalists, caught off guard, asked him to go in and do it again so they could get pictures, and he told my mother what he’d done I remember dancing around the room chanting that my father had “got” the Committee. I also grew up singing, “Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union.” So when I read that all over the United States, laws are being proposed that will blacklist activists, organizations, businesses and institutions who exercise their First Amendment right to use economic boycott as a tool of political persuasion to end the egregious violations of Palestinian human rights by the Israeli state and sectors of Israeli society, that’s the song that goes through my head. The proposers of these laws believe with ferocity that the only possible way to prevent a repetition of the Nazi attempted genocide and keep Jewish people safe in the world is to unconditionally support a militarized and racist state dominated by Jews, in which non-Jewish Palestinians (Yes, Susie, there are Palestinian Jews) can be dispossessed, culturally and historically erased, forced into permanent unemployment, beaten, gassed, starved, shot, imprisoned without trial, segregated and murdered with impunity, and that therefore, any attempt to stop these horrible abuses is anti-Semitic. That not killing (non-Jewish) Palestinians means agreeing to the killing of Jews. A terrified determination not to be victims wedded to European racist colonial entitlement has become the terrifying victimization of others.  Never for one moment of my life have I believed that exclusive state power for Jews makes me safer. Never for one moment have I believed there is not enough freedom, or safety, or peace to go around, and that my wellbeing as a Jew depends on the suffering of Palestinians who are not Jews. Never for one moment have I believed that my great-grandfather’s sister and brother, their spouses and children, who were slaughtered by Einsatzgruppen on May 19, 1942 in a small village in the Ukraine, would be anything but horrified and outraged that their suffering and deaths are used to justify the suffering and deaths of Palestinian families, or that they would fail to recognize oppression when they saw it. My people were the ones who took and read the pamphlets brought in secret to the shtetls by traveling organizers. They were the ones who believed that only in the universal solidarity of working people would any of us find security. They were proudly Jewish, proudly socialist and communist on both sides of the Atlantic, and because they knew that Jews too, could be slumlords and sweatshop owners, because my great-grandmother once led a strike in a shop her husband managed, because strikes and boycotts and laying bare the bones of injustice was what they did, I am quite sure that they would be proud that I won’t participate in cultural work sponsored by Israeli institutions though I will happily collaborate with Israeli artists who share my values, that I will not buy a Hewlett-Packard printer until they no longer service the Israeli repressive apparatus, and that the candles I light as I remember them were made in California and benefit social justice projects in Israel/Palestine. It may be that these things will lose me invitations to speak in some places, but I’ll speak in others. My Jewish great-grandfather had to pass checkpoints to get to work, my Puerto Rican grandmother had to pass for Italian and hide her family to get apartments, and my parents had to learn to grow lettuce and sell it from the back of a pickup truck because being committed to social justice in the 1950s meant you couldn’t get a job, but none of that stopped us. Because genocide didn’t change our minds. We still believe that justice for all is the only guarantee.

So, I will fight as best I can to stop these blacklist laws from passing, but if they do, I will open up my mouth and sing, “Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the boycott.”

1 Comment

Irene

1/12/2016 09:45:22 pm

Thank you for sharing your family's powerful stories. Energizing and inspiring!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed