Short Stories

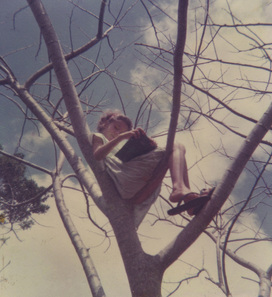

Cosecha and Other Stories is my first short fiction collection, co-authored with my mother, Rosario Morales, but in between essays, poems and speeches, I've been writing short stories for a long time. When I was little, our parents read aloud to me and my brother every night, we'd listen to novels, a chapter at a time, on the shortwave radio, and we would act out Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, and our own complicated adventures. Although I played for hours in the lush rainforest, I spent many hours of perched, in brilliant, tropical sunlight, in the upper branches of trees, or curled up in my bunk bed while the rain battered the roof, transported by the magic of books. Below are tastes of some of the stories that will appear in Cosecha. You can also read the full story, "Dulce de Naranja"

Story excerpts from Cosecha :

A Remedy for Heartburn (First published in Ms. , 1991.)

Puerto Rican relatives in NYC.

Puerto Rican relatives in NYC.

Our people have always been good at digesting even the most indigestible items on life's menu. Insults that would give a conquistador a heart attack-- we have learned to wipe them off our faces and put the handkerchief away for later consideration. Sometimes our pockets bulge with insults, and personally, I have a little red leather coin purse that I had to quit using because it wouldn't close anymore. There were so many insults and so few coins that I was always turning up something nasty whenever I dug around for a subway token. When you run out of storage space, sometimes a hiss or sneer or some offhand and cheerful piece of disrespect goes down your throat and your stomach has to deal with it. It's not easy. It gives you heartburn like you wouldn't believe, but we can do it. All of us are experts.

As for this jaw-breaking language that gets pushed into our mouths every time we ask for a piece of bread, we're the best there is at digesting that. We roll it around in our sweet tropical saliva and spit it back, sweeter and sharper and altogether more sabroso. Everything they dish out to us, we soften and satirize with our acrobatic tongues. We wash with Palmolíveh and brush with super-white Colgáteh. We rub Vicks Vaporú on our chests when we get a cold, and halfway through each day of hard work and boredom, we stop and have some lonche. Not at home on weekends. We never have lonche at home. But weekdays when we step into some hallway with a counter and six red stools and order a sánguich--that's lonche.

As for this jaw-breaking language that gets pushed into our mouths every time we ask for a piece of bread, we're the best there is at digesting that. We roll it around in our sweet tropical saliva and spit it back, sweeter and sharper and altogether more sabroso. Everything they dish out to us, we soften and satirize with our acrobatic tongues. We wash with Palmolíveh and brush with super-white Colgáteh. We rub Vicks Vaporú on our chests when we get a cold, and halfway through each day of hard work and boredom, we stop and have some lonche. Not at home on weekends. We never have lonche at home. But weekdays when we step into some hallway with a counter and six red stools and order a sánguich--that's lonche.

That's hard to digest, too, tasteless white bread, a smear of mayonnaise, a few wrinkled slices of ham or old-shoe beef, a square of what these people were actually not embarrassed to call American cheese and some kind of a pale green leaf. But our people have hard stomachs. Hunger makes people more like goats. I've known old men who lived for months on end on nothing but the malanga they dug out of other people's land. The USDA surplus lunches they served at our grade school comedor were excellent training for the immigrant eater's lonche break. The kids used to say the beans tasted of cucaracha, they'd been sitting in some warehouse so long. As for the lukewarm powdered milk we gagged on, it was what each of us was told to be grateful for. Iit would make us strong and healthy, and, if we got good grades and had respect for our elders, it would make us worthy of our citizenship in that great nation los Estados Unidos, where everything good came from.

First Snow (Unpublished.)

"Nights while the stars swung overhead we leaned in slow, delicious free fall toward each other’s arms, knowing we would arrive in our own good time. Apples, berries, nuts, pumpkins, late corn all spilled their abundance from the roadside stands. Around us the trees glowed in the colors of sun-ripe fruit, flickering and bright as faces turned to a hidden fire. But all the time the roots were reaching for a place deeper than the approaching frost, a race against the tilt of the earth's axis.

We filled our room with the litter of the shedding trees, each new magenta or salmon leaf as astonishing as the last. In your long grey coat you walked in the flaming woods for hours, coming back silent, full of autumn, the season neither of us had ever seen before. And you waited for snow. Growing up in Houston, and this last year in Israel, you had never seen it fall. You wanted to be outside when it began, you said, (like girls planning their first embraces), to see the first flakes spinning down and lift your face to the kiss of winter."

We filled our room with the litter of the shedding trees, each new magenta or salmon leaf as astonishing as the last. In your long grey coat you walked in the flaming woods for hours, coming back silent, full of autumn, the season neither of us had ever seen before. And you waited for snow. Growing up in Houston, and this last year in Israel, you had never seen it fall. You wanted to be outside when it began, you said, (like girls planning their first embraces), to see the first flakes spinning down and lift your face to the kiss of winter."

Vivir Para Tí (First published in The American Voice, 1991.)

The afternoon pressed into her like the palm of a huge hand, hot and damp against her thickening body. ¡Ay! Me sofoco. She stood in the doorway, her hand on her hip, watching two hens stalk the dirt, tipping their heads to look for stray kernels of corn. She reached into her pocket for a handful of grain and threw it to them. More chickens came scurrying out from under the bushes. Leaning against the wood she looked out at the hills, falling away softly, stifled, too, by the dense air. The baby pressed relentlessly, hard as a green orange, against her breastbone, crushing her breath.

In the dim room behind her the television droned on to itself, casting a blue light into the corners. The passionate voices and shadowy faces were flattened by the brilliant light. She couldn't remember the characters' names. Was it the two 'o clock novela or the three 'o clock? You didn't remember the people, just the situations. The music rose and then changed abruptly. Luz glanced back over her shoulder into the dark room.

A cheerful young mother and her small daughter, in matching aprons, sat at a table in a brand new kitchen, pouring the best selling brand of tomato sauce into Papá's beans, stirring, and singing a little song together. After a moment Papá walked in the door from work, wearing a shirt and tie, smiling and carrying a briefcase. He kissed the wife and child, sat down and tasted the beans, and smiled with satisfaction. Then a dancing tomato sauce can wiggled across the screen and the picture faded. Luz used a different brand.

She walked herself to the stove and lit the flame under a pot of peeled green bananas, then backed away, fanning herself with the flat of her hand. The children would be home from school soon. She heard the jeep pull in and stop beside the house. Her father was back early. She knew as soon as she heard him coughing and muttering that he'd been drinking. He snarled and kicked at one of the chickens, and it scurried, clacking, into the bushes. I wish, panic rising like the perpetual heartburn, making her gag, I wish I could disappear.

In the dim room behind her the television droned on to itself, casting a blue light into the corners. The passionate voices and shadowy faces were flattened by the brilliant light. She couldn't remember the characters' names. Was it the two 'o clock novela or the three 'o clock? You didn't remember the people, just the situations. The music rose and then changed abruptly. Luz glanced back over her shoulder into the dark room.

A cheerful young mother and her small daughter, in matching aprons, sat at a table in a brand new kitchen, pouring the best selling brand of tomato sauce into Papá's beans, stirring, and singing a little song together. After a moment Papá walked in the door from work, wearing a shirt and tie, smiling and carrying a briefcase. He kissed the wife and child, sat down and tasted the beans, and smiled with satisfaction. Then a dancing tomato sauce can wiggled across the screen and the picture faded. Luz used a different brand.

She walked herself to the stove and lit the flame under a pot of peeled green bananas, then backed away, fanning herself with the flat of her hand. The children would be home from school soon. She heard the jeep pull in and stop beside the house. Her father was back early. She knew as soon as she heard him coughing and muttering that he'd been drinking. He snarled and kicked at one of the chickens, and it scurried, clacking, into the bushes. I wish, panic rising like the perpetual heartburn, making her gag, I wish I could disappear.

Ecuadoran tv commercial.

Ecuadoran tv commercial.

A cheerful young mother and her small daughter, in matching aprons, sat at a table in a brand new kitchen, pouring the best selling brand of tomato sauce into Papá's beans, stirring, and singing a little song together. After a moment Papá walked in the door from work, wearing a shirt and tie, smiling and carrying a briefcase. He kissed the wife and child, sat down and tasted the beans, and smiled with satisfaction. Then a dancing tomato sauce can wiggled across the screen and the picture faded. Luz used a different brand.

She walked herself to the stove and lit the flame under a pot of peeled green bananas, then backed away, fanning herself with the flat of her hand. The children would be home from school soon. She heard the jeep pull in and stop beside the house. Her father was back early. She knew as soon as she heard him coughing and muttering that he'd been drinking. He snarled and kicked at one of the chickens, and it scurried, clacking, into the bushes. I wish, panic rising like the perpetual heartburn, making her gag, I wish I could disappear.

She walked herself to the stove and lit the flame under a pot of peeled green bananas, then backed away, fanning herself with the flat of her hand. The children would be home from school soon. She heard the jeep pull in and stop beside the house. Her father was back early. She knew as soon as she heard him coughing and muttering that he'd been drinking. He snarled and kicked at one of the chickens, and it scurried, clacking, into the bushes. I wish, panic rising like the perpetual heartburn, making her gag, I wish I could disappear.

Dry salt codfish, bacalao.

Dry salt codfish, bacalao.

"Where the hell's my food!"

"Its not ready yet. I didn't expect you until later."

"So you think I should be out working in this hell-heat? Stupid girl. Look at you! What a mess!"

Think of a knife, she told herself slowly. Imagine a knife gutting him like a codfish that comes flattened, stiff, spread open, crusted with salt, packed in boxes. You rip the spines out with the edge of a blade. Her eyes went flat, trying to reflect nothing at all for his fury to latch onto. Once, when her belly was first showing, he had seen something stir in her eye and slammed her hard against the wall, making her teeth crack against each other. Her ribs had ached for days. He had tried to hit her in the stomach, but she'd curled herself tight, and spitting curses he'd gone back out, and come back too drunk for trouble.

Her father sat down on the vinyl couch and stared at the flickering screen where two lovers were kissing passionately. Stay tuned to this channel for more romance, said the announcer. In just a few moments María Estér stars in... and a husky woman's voice whispered, Vivir....Para Ti. To live...for you.

"Its not ready yet. I didn't expect you until later."

"So you think I should be out working in this hell-heat? Stupid girl. Look at you! What a mess!"

Think of a knife, she told herself slowly. Imagine a knife gutting him like a codfish that comes flattened, stiff, spread open, crusted with salt, packed in boxes. You rip the spines out with the edge of a blade. Her eyes went flat, trying to reflect nothing at all for his fury to latch onto. Once, when her belly was first showing, he had seen something stir in her eye and slammed her hard against the wall, making her teeth crack against each other. Her ribs had ached for days. He had tried to hit her in the stomach, but she'd curled herself tight, and spitting curses he'd gone back out, and come back too drunk for trouble.

Her father sat down on the vinyl couch and stared at the flickering screen where two lovers were kissing passionately. Stay tuned to this channel for more romance, said the announcer. In just a few moments María Estér stars in... and a husky woman's voice whispered, Vivir....Para Ti. To live...for you.