As a child, I was especially drawn to the intoxicating language of Dylan Thomas, including his "A Child's Christmas in Wales." I always wanted to write my own, Puerto Rican version. "Dulce de Naranja" was written for an anthology of Christmas stories by well known Latin@ authors, Las Christmas. My version is complicated by the fact that I am also a Jew. I was angry and dismayed to discover that all reference to my Jewishness was cut from the Spanish version of the book. Apparently the editors assumed that Spanish speaking readers would not include anyone like me, or perhaps that in the great multilingual web of latinidades, only the English speakers can handle the religious and cultural diversity of Latin America. Here is the full story as I wrote it.

Dulce de Naranja

In Puerto Rico, Las Navidades is a season, not a single day. Early in December, with the hurricane season safely over, the thick autumn rains withdraw and sun pours down on the island uninterrupted. This will be a problem by March, when the reservoirs empty, and the shores of Lake Luchetti show wider and wider rings of red mud, until the lake bottom curls up into little pancakes of baked clay and the skeletons of long drowned houses are revealed. Then, people wait anxiously for rain, and pray that the sweet, white coffee blossoms of April don’t wither on the branch. But during Navidades, the sun shines on branches heavily laden with hard green berries starting to ripen and turn red. Oranges glow on the trees, aguinaldos dominate the airwaves of Radio Café and women start grating yuca and plantain for pasteles, and feeling up the pigs and chickens, calculating the best moment for the slaughter.

It was 1962 or maybe 1965. Any one of those years. Barrio Indiera Baja of Maricao and Barrio Rubias of Yauco are among the most remote inhabited places on the island, straddling the crest of the Cordillera Central among the mildewed ruins of old coffee plantations, houses and sheds left empty when the tides of international commerce withdrew. A century ago, Yauco and Maricao fought bitterly to annex this highland acreage from one another, at a time when Puerto Rican coffee was the best in the world. But Brazil flooded the market with cheaper, faster growing varieties. There were hurricanes and invasions and the coffee region slid into decline. In the 1960s of my childhood most people in Indiera still worked in coffee, but everyone was on food stamps except the handful of hacendados, and young people kept leaving for town jobs or for New York and Connecticut.

Those were the years of modernization. Something was always being built or inaugurated — dams, bridges, new roads, shopping centers and acres of housing developments. Helicopters crossed the mountains installing electrical poles in places too inaccessible for trucks (keeping an eye out for illegal rum stills.) During my entire childhood the aqueducto, the promise of running water, inched its way towards us with much fanfare and very little result. When the pipes were finally in place, the engineers discovered that there was rarely enough pressure to drive the water up the steep slopes north of the reservoir. About once a month the faucets, left open all the time, started to sputter. Someone called out "aqueduuuuucto" and everyone ran to fill their buckets before the pipes went dry again.

Navidades was the season for extravagance in the midst of hardship. Food was saved up and then lavishly spread on the table. New clothing was bought in town or made up by a neighbor and furniture brought home, to be paid off in installments once the harvest was in.

One of those years, her husband bought Doña Gina an indoor stove with an oven, and all the neighbors turned out to see. They were going to roast the pig indoors! Not a whole pig, of course, but I was there watching when Don Lencho slashed the shaved skin and rubbed the wounds with handfuls of mashed garlic and fresh oregano, achiote oil and vinegar, black pepper and salt. Doña Gina was making arroz con dulce, tray after tray of cinnamon-scented rice pudding with coconut. The smells kept all the children circling around the kitchen like hungry sharks.

Navidades was the season for extravagance in the midst of hardship. Food was saved up and then lavishly spread on the table. New clothing was bought in town or made up by a neighbor and furniture brought home, to be paid off in installments once the harvest was in.

One of those years, her husband bought Doña Gina an indoor stove with an oven, and all the neighbors turned out to see. They were going to roast the pig indoors! Not a whole pig, of course, but I was there watching when Don Lencho slashed the shaved skin and rubbed the wounds with handfuls of mashed garlic and fresh oregano, achiote oil and vinegar, black pepper and salt. Doña Gina was making arroz con dulce, tray after tray of cinnamon-scented rice pudding with coconut. The smells kept all the children circling around the kitchen like hungry sharks.

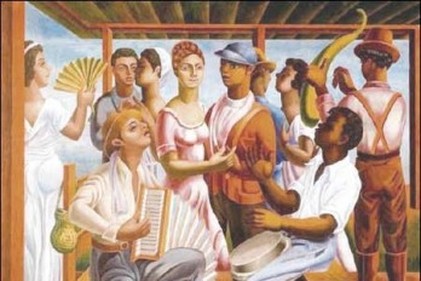

Merengue. Jaime Colson, 1938.

This was before every house big enough for a chair had sprouted a TV antenna. My brother and I went down to the Canabal house to watch occasional episodes of Bonanza dubbed into Spanish: I liked to watch the lips move out of sync with the voice that said "Vámonos, Hoss!" And by 1966 there would be a TV in the seventh grade classroom at Arturo Lluberas Junior High, down near Yauco, where the older girls would crowd in to watch "El Show del Mediodía." But in Indiera and Rubias nobody was hooked on TV Christmas specials yet. When the season began, people still tuned up their cuatros and guitars, took down the güiros and maracas and started going house-to-house looking for free drinks. So while Don Lencho kept opening the oven to baste the pig, Chago and Nestor and Papo played aguinaldos and plenas and Carmencita improvised lyrics back and forth with Papo, each trying to top the other in witty commentary, the guests hooting and clapping when one or the other scored a hit. No one talked much about Cheito and Luis away in Viet Nam, or Adita's fiancé running off with a pregnant high school girl a week before the wedding or Don Toño coughing up blood all the time. "Gracias a Dios" said Doña Gina, "Aqui estamos."

During Navidades the cars of city relatives started showing up parked in the road next to the red and green jeeps. My girlfriends had to stay close to home and wear starched dresses, and the boys looked unnaturally solemn in ironed white shirts, with their hair slicked down. Our relatives were mostly in New York, but sometimes a visitor came all that way, announced ahead of time by letter, or, now and then, adventurous enough to try finding our farm with just a smattering of Spanish and a piece of paper with our names.

During Navidades the cars of city relatives started showing up parked in the road next to the red and green jeeps. My girlfriends had to stay close to home and wear starched dresses, and the boys looked unnaturally solemn in ironed white shirts, with their hair slicked down. Our relatives were mostly in New York, but sometimes a visitor came all that way, announced ahead of time by letter, or, now and then, adventurous enough to try finding our farm with just a smattering of Spanish and a piece of paper with our names.

Arroz con gandules.

The neighbors grew their own gandules and plantain, but except for a few vegetables we didn't farm our land. My father drove to San Juan every week to teach at the university, and did most of our shopping at the Pueblo supermarket on the way out of town. Sometimes all those overflowing bags of groceries weighed on my conscience, especially when I went to the store with my best friend Tita and waited while she asked Don Paco to put another meager pound of rice on their tab. My father was a biologist and a commuter. This was how we got our frozen blintzes and English muffins, fancy cookies and date nut bread.

Spanish turrón

But during Navidades it seemed, for a little while, as if everyone had enough. My father brought home Spanish turrón- — sticky white nougat full of almonds, wrapped in thin edible layers of papery white stuff. The best kind is the hard turrón you have to break with a hammer. Then there were all the gooey, intensely sweet fruit pastes you eat with crumbly white cheese. The dense, dark red-brown of guayaba, golden mango, sugar-crusted pale brown batata and dazzlingly white coconut. And my favorite, dulce de naranja, a tantalizing mix of bitter orange and sugar, the alternating tastes always startling on the tongue. We didn’t eat pork, but my father cooked canned corned beef with raisins and onions and was the best Jewish tostón maker in the world.

Navidades at my maternal grandparents' in NYC

Christmas trees were still a strange gringo custom for most of our neighbors, but each year we picked something to decorate, this household of transplanted New Yorkers — my Puerto Rican mother, my Jewish father and the two, then three of us "Americanito" kids growing up like wild guayabas on an overgrown and half-abandoned coffee farm. One year we cut a miniature grove of bamboo and folded dozens of tiny origami cranes in gold and silver paper to hang on the branches. Another year it was the tightly rolled, flame red flowers of señorita with traditional, shiny Christmas balls glowing among the lush green foliage. Sometimes it was boughs of Australian pine hung with old ornaments we brought with us from New York in 1960, those pearly ones with the inverted cones carved into their sides like funnels of fluted silver and gold light.

The only telephone was the one at the crossroads, which rarely worked, so other than my father’s weekly trip to San Juan, the mail was our only link with the world outside the barrio. Every day during las Navidades when my brother and I stopped at the crossroads for the mail there would be square envelopes in bright colors bringing Season’s Greetings from far away people we'd never met. But there were also packages. We had one serious sweet tooth on each side of the family. Every year my Jewish grandmother sent metal tins full of brightly wrapped toffee in iridescent paper that my brother and I saved for weeks. Every year my Puerto Rican grandfather sent boxes of Jordan almonds in sugary pastels and jumbo packs of Hershey's kisses and Tootsie rolls.

Of course, this was also the season of rum, of careening jeep loads of festive people in constant motion up and down the narrow twisting roads of the mountains. You could hear the laughter and loud voices fade and blare as they wound in and out of the curves. All along the roadsides were shrines, white crosses or painted rocks with artificial flowers and the dates of horrible accidents: head-on collisions when two jeeps held onto the crown of the road too long; places where drivers mistook the direction of the next dark curve and rammed into a tree, or plummeted, arcing into the air and over the dizzying edge, to crash down among the broken branches of citrus and pomarosa leaving a wake of destruction. Some of those ravines still held the rusted frames of old trucks and cars no one knew how to retrieve after the bodies were taken home for burial.

It was rum, the year my best friend's father died. Early Navidades, just coming into December and parties already in full swing. Chiqui, Tita, Chinita and I spent a lot of time out in the road, while inside, women in black dresses prayed, cleaned and cooked. Every so often one of them would come out on the porch and call Tita or Chiqui, who were cousins, to get something from the store, or go down the hill to the spring to fetch another couple of buckets of water.

It was rum, the year my best friend's father died. Early Navidades, just coming into December and parties already in full swing. Chiqui, Tita, Chinita and I spent a lot of time out in the road, while inside, women in black dresses prayed, cleaned and cooked. Every so often one of them would come out on the porch and call Tita or Chiqui, who were cousins, to get something from the store, or go down the hill to the spring to fetch another couple of buckets of water.

Puerto Rican mountain schoolgirls.

No one in Indiera was called by their real name. It was only in school, when the teacher took attendance, that you found out all those Tatas and Titas, Papos and Juniors were named Milagros and Carmen María, Jose Luis and Dionisio. The few names people used became soft and blurred in our mouths, in the country Puerto Rican Spanish we inherited from Andalucian immigrants who settled in those hills centuries ago and kept as far as they could from Church and State alike. We mixed yanqui slang with the archaic accents of the sixteenth century so that Ricardo became Hicaldo while Wilson turned into Güilsong. Every morning the radio announced all the saints whose names could be given to children born that day, which is presumably how people ended up with names like Migdonio, Eduvigis and Idelfonso.

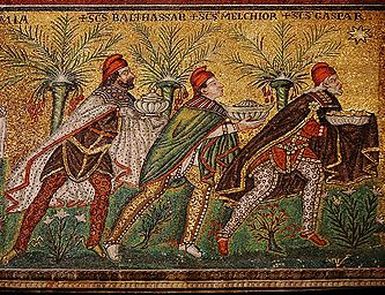

Anyway, Tata's father was dying of alcoholism, his liver finally surrendering to forty or fifty years of heavy drinking and perhaps his heart collapsing under the weight of all the beatings and abuse he had dished out to his wife and fourteen children. Tata was his youngest child — ten, scrawny, fast on her feet. Her city nieces and nephews were older, but in the solemn days of waiting for death, she played her status for all it was worth, scolding them for laughing or playing, reminding them that she was their aunt, and must be respected. All day the women swept and washed and cooked and in the heat of the afternoon sat sipping coffee, talking softly on the porch. In our classroom, where we also awaited news of the death, we were deep into the usual holiday rituals of public school. The girls cut out poinsettia flowers from red construction paper and the boys got to climb on chairs to help Meesee Torres hang garishly colored pictures of the Three Kings above the blackboard. We practiced singing "Alegria, Alegria, Alegria" and during Spanish class we read stories of miraculous generosity and goodwill.

Late one Tuesday afternoon after school, we heard the wailing break out across the road and the next day Meesee Torres made us all line up and walk up the hill to Tata's house to pay our respects. We filed into their living room, past the open coffin, each placed a single flower in the vase Meessee had brought, then filed out again. What astonished me was how small Don Miguel looked, nested in white satin, just a little brown man without those bulging veins of rage at his temples and the heavy hands waiting to hit.

The next night the velorio began. The road was full of jeeps and city cars, and more dressed up relatives than ever before spilled out of the little house. For three days people ate and drank and prayed and partied, laughing and chatting, catching up on old gossip and rekindling ancient family arguments. Now and then someone would have to separate a couple of drunken men preparing to hit out with fists. Several of the women had ataques, falling to the ground and tearing their hair and clothing.

Late one Tuesday afternoon after school, we heard the wailing break out across the road and the next day Meesee Torres made us all line up and walk up the hill to Tata's house to pay our respects. We filed into their living room, past the open coffin, each placed a single flower in the vase Meessee had brought, then filed out again. What astonished me was how small Don Miguel looked, nested in white satin, just a little brown man without those bulging veins of rage at his temples and the heavy hands waiting to hit.

The next night the velorio began. The road was full of jeeps and city cars, and more dressed up relatives than ever before spilled out of the little house. For three days people ate and drank and prayed and partied, laughing and chatting, catching up on old gossip and rekindling ancient family arguments. Now and then someone would have to separate a couple of drunken men preparing to hit out with fists. Several of the women had ataques, falling to the ground and tearing their hair and clothing.

The first night of the velorio was also the first night of Hanukkah that year. While Tata went to church with her mother to take part in rosarios and novenas and Catholic mysteries I knew nothing of, my family sat in the darkened living room of our house lighting the first candle on the menorah, the one that lights all the others. Gathered around that small glow, my father told the story of the Macabees who fought off an invading empire, while across the road, Tata's family laughed together, making life bigger than death. I remember sitting around the candles, thinking of those ancient Jews hanging in for thirty years to take back their temple, what it took to not give up; and of all the women in the barrio raising children who sometimes died and you never knew who would make it and who wouldn't, of people setting off for home and maybe meeting death in another jeep along the way. And in the middle of a bad year, a year of too much loss, there were still two big pots of pasteles and a house full of music and friends. Life, like the aqueducto, seemed to be unpredictable, maddening and sometimes startlingly abundant.

That night I lay awake for a long time in the dark, listening to life walking towards me. Luis would never come home from Viet Nam and Cheito would come home crazy, but the war would end someday and most of us would grow up. My father would be fired from the university for protesting that war, and we would be propelled into a new life, but I would find lifelong friends and new visions for myself in that undreamt of city. Death and celebration, darkness and light, the miraculous star of the Three Kings and the miracle of a lamp burning for eight days on just a drop of oil. So much uncertainty and danger and so much stubborn faith. And somewhere out there in the dark, beyond the voices of Tata's family still murmuring across the road, the three wise mysterious travelers were already making their way to me, carrying something unknown, precious, strange.

©2006 Aurora Levins Morales

©2006 Aurora Levins Morales