|

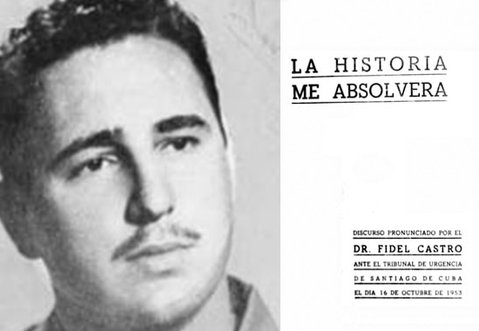

One of my favorite songwriters, Cuban Pablo Milanes, wrote: Lo que brilla con luz propia, nadie la puede apagar, su brillo puede alcanzar la oscuridad de otras costas. What shines with its own light, no one can extinguish, its brilliance reaches the darkness of other shores. I was born on one of those other shores, in what a few weeks ago, one Cuban revolutionary described as “grey times.”  I never saw Havana in those years. I only knew by rumor that it was a playground for the rich and corrupt, run by the US mob and the CIA, a place where children begged in the streets and shined the shoes of foreigners for a bite of bread, where Black Cubans couldn’t go in the front doors of night clubs that served up their music to white Cubans and foreign tourists. My friends who were children then remember the tortured bodies of union organizers, student activists, anyone who dared to protest, dumped late at night in the quiet streets of the suburbs, remember their terror of the police. Across Latin America, dictatorships flourished, and even the most basic striving, for enough to eat, for a roof overhead, were met with gunfire, disappearance, beatings, people dragged into jail cells buried so far from sight no one ever saw them again. When I was young, these stories floated above my head, spoken among adults who met in our living room, between my parents. The names of overthrown presidents, assassinated leaders and massacres hung in the air, while anti-colonial movements erupted and were suppressed, erupted and were suppressed. Young Cubans rose up to take the Moncada barracks and were killed, tortured, exiled and a young lawyer promised that history would absolve him. A handful of small victories and a litany of defeats, of broken branches piled high, waiting for a spark.

0 Comments

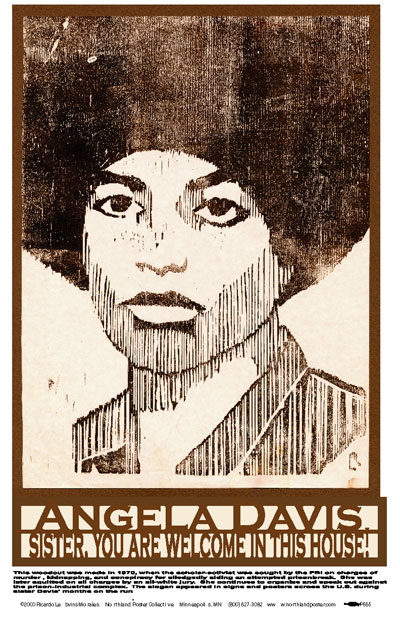

Poster by Ricardo Levins Morales Poster by Ricardo Levins Morales For those who don’t know, right after the election, someone proposed wearing safety pins to indicate that we are allies to anyone being attacked in the post-election upsurge of hate crimes, and while many embraced it, many also criticized it as superficial, and debate over this tactic continues to rage. There are several things that this very heated argument ignores. Many People of Color rightly critique the possibility that white liberals will wear a pin as a form of self-soothing, feeling brave for taking a largely symbolic action, without actually doing the necessary work of building ally muscle. But it seems many assume that these are the only people who would consider wearing a safety pin as a statement of intent, that anyone wearing one is doing nothing else. It’s an assumption based in fury and frustration, and utterly understandable but inaccurate. Seasoned and dedicated allies also have reasons to wear them. I have been a lifelong radical for whom expressions of solidarity are as natural as breath. I am old enough to remember the window signs we put up when Angela Davis was in hiding that said “Sister, you are welcome in this house.” Of course, she wasn’t going to knock on our door just because of a sign, and we didn’t expect her to. We were speaking to each other and to the state, affirming our commitments, and making a public statement of alliance. It was one small part of the organizing work we were doing in support of Black Liberation, and it mattered. Symbolic actions have power to inspire, to build connection, to express an idea that moves people forward. Secondly, four highly targeted people in my life have told me that seeing the pins on people’s clothing makes them feel safer and lifts their spirits, and that’s enough of a reason for me. But I think the most important point being missed is that in times like these, we need each of us to take a step forward from wherever we are. People are scared, angry, and feeling urgent, wanting our allies to have already arrived where we need them to be, and ready to be scathing towards those who are not. I am not suggesting that anyone be less angry. Rage is appropriate. But no matter how impatient they make us, directing our rage at potential allies who are taking their first baby steps is the wrong target. Jane Speed 1910-1958  This is Jane. Jane lives in Alabama with her wealthy white family. In the 1920s, Jane’s mother, Mary Martin Craik Speed, (Dolly,) takes her to Vienna to study. Jane sees fascists attacking workers’ housing coops and joins Austrian communists' anti-fascist organizing. Jane thinks about southern sharecroppers. She reads George Bernard Shaw’s The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism. See Jane get radicalized. Think, Jane, think! Say these words when you lie down and when you rise up, when you go out and when you return. In times of mourning and in times of joy. Inscribe them on your doorposts, embroider them on your garments, tattoo them on your shoulders, teach them to your children, your neighbors, your enemies, recite them in your sleep, here in the cruel shadow of empire: Another world is possible. Thus spoke the prophet Roque Dalton: All together they have more death than we, but all together, we have more life than they. There is more bloody death in their hands than we could ever wield, unless we lay down our souls to become them, and then we will lose everything. So instead, imagine winning. This is your sacred task. This is your power. Imagine every detail of winning, the exact smell of the summer streets in which no one has been shot, the muscles you have never unclenched from worry, gone soft as newborn skin, the sparkling taste of food when we know that no one on earth is hungry, that the beggars are fed, that the old man under the bridge and the woman wrapping herself in thin sheets in the back seat of a car, and the children who suck on stones, nest under a flock of roofs that keep multiplying their shelter. Lean with all your being towards that day when the poor of the world shake down a rain of good fortune out of the heavy clouds, and justice rolls down like waters. Defend the world in which we win as if it were your child. It is your child. Defend it as if it were your lover. It is your lover. When you inhale and when you exhale breathe the possibility of another world into the 37.2 trillion cells of your body until it shines with hope. Then imagine more. Imagine rape is unimaginable. Imagine war is a scarcely credible rumor That the crimes of our age, the grotesque inhumanities of greed, the sheer and astounding shamelessness of it, the vast fortunes made by stealing lives, the horrible normalcy it came to have, is unimaginable to our heirs, the generations of the free. Don’t waver. Don’t let despair sink its sharp teeth Into the throat with which you sing. Escalate your dreams. Make them burn so fiercely that you can follow them down any dark alleyway of history and not lose your way. Make them burn clear as a starry drinking gourd Over the grim fog of exhaustion, and keep walking. Hold hands. Share water. Keep imagining. So that we, and the children of our children’s children may live _______ Feel free to share this poem, but please do so as a link to this blog page. Poetry is labor. Please respect it. Join Aurora's mailing list. Donate to support Aurora's work.

The other day I was talking with Qassim about what it's like to be Muslim in New York City right now. He said people in his community are scared, depressed, lying low, feeling alone. We talked about the man on Southwest Airlines who was pulled off the plane because a woman heard him say Inshallah and thought it was a terrorist plot. How when a white Christian commits mass murder, it's about his terrible childhood, his disturbed adolescence, bad influences, and when it a Muslim it's because Muslims are just that way. I let him know that I am clear that US wars and CIA maneuvers create young people filled with desperation and rage and weapons.  I told him I am a Puerto Rican Jew , a member of Jewish Voice for Peace, and that we're working to get his back and the backs of his people, fighting Islamophobia. We talked about Syrian refugees, about the ill informed bigotry that can''t distinguish between terrorists and their victims. He said he knows the suspicion in people's eyes is rooted in ignorance and sounded sad. I asked him about conditions in Pakistan, and he told me how they flip back and forth between military dictators and democratic elections, how unstable it is. I asked him about the 1947 partition--had it made things better or worse between Muslims and Hindus. Worse, he thinks. He's going back for a visit soon. It takes 20 hours to get there, so he stays for a couple of months when he goes. We were getting close to my destination, so I reminded him that some of us are actively defending Muslims. When it feels like you're alone, I said, remember that you're not.  "Puerto Rico first. To hell with the debt." "Puerto Rico first. To hell with the debt." When I met José we talked about colonialism , direct and neo, in the Caribbean, about the armed robbery of so called Third World Debt, how the crisis in Puerto Rico is like having your wallet taken at gunpoint and then the robber lends your money back to you at high interest, and when you said you have to eat, says no, you can't eat, you owe me money. We talked about government corruption, about the Puerto Rican police being the most corrupt and violent under US jurisdiction, about the US invasion of the Dominican Republic, that the planes flew over my house, about privatization, and Latin America under siege, and how, as Caribbean people, we have a hard time with winter and northern individualism.  Guyanese opposition coalition. Guyanese opposition coalition. Hemraj is from Guyana. His name means king of gold. He says there are lists of names depending on the day you are born. I tell him the radio in rural Puerto Rico used to read off lists of saints' names for babies born on that day. He tells me about the recent elections which shifted power from the Indo-Guyanese like himself to a coalition led by Afro-Guyanese. To him it's all turmoil and disruption and he doesn't want to go home til things settle down. It makes me curious enough to look it up when I get home. João is critical of Dilma's government although he liked Lula, but says communists are destroying Brazil. Musa is a direct descendant of Mansa Musa, ruler of Mali in the 1300s. He tells me his last name comes from one specific place in Mali and everyone in Mali knows this.  Dushambe, Tajikistan Dushambe, Tajikistan Farrukh is from Tajikistan and I ask about the boundaries between Muslim controlled and Christian controlled regions where Asia and Europe meet, test my knowledge of geography, learn about his home in Dushanbe. A few days later, when I meet a Bokharan Jew, a people rooted for two thousand years in what is now Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, I know where it is, can visualize what he tells me, that at the same time my Ukrainian Ashkenazi people were being evacuated eastward, away from the Nazi invasion of the USSR, his were being sent to the front with the Red Army and junk weapons. I still smile about my conversation with a Black South African Jew, how we were each trying to tell the other about Jews of Color and surprised each other into laughter, how we talked about Palestine and his hometown of Soweto, how I told him I had been part of the anti-Apartheid movement here and we thanked each other, and when our time was up, he embraced me, and called me his sister. My father, Richard Levins, who died on January 19, was an atheist, and I couldn't bring myself to say a traditional kaddish for him, but he did believe in forces greater than himself, and I decided to write my own kaddish celebrating his faith in their endurance and hopefulness. Joyously celebrated be the infinite complexity and beauty of the universe, its endless dialectic, its loops of positive and negative feedback, equilibrium and change, its constant evolution; and celebrated be human creativity and solidarity and courage. May they establish liberation in our lifetimes and in our days and in the lives of all peoples everywhere, speedily and soon, and let us say, ¡Que viva!

Praise to the great dialectic of change always unfolding possibilities. May the deep wells of humanity and hope within us gush forth into the world and may there be principled unity and immense and powerful coalitions, clearheaded analysis and breathtaking vision, and practical, hard work done together and with joy. May the local and the global embrace, may the personal and political embrace, may intellect, emotion and flesh dance together. May our deepest desire for connection dissolve all factions and wash away all unnecessary conflict. Blessed and praised be solidarity, extolled and honored beyond all the songs and chants, manifestos and movements that have ever been crafted, for it is our greatest hope and we must cultivate it in all we do, and let us say ¡Que viva! May all who are bound up in the toils of greed for power and wealth, and all who are trapped in the fear of scarcity, in selfish individualism and the short term strategies of desperation, and all who are confused by privilege and wounded by the ruthless heartlessness of oppression, be released, to join in the common good of us all which is far greater than any other reward. May liberation arise abundant and universal from our own hands and hearts and minds; may there be peace and justice and life for us, and for all beings, and let us say ¡Que viva! May we whose love and labor bring life sustaining food forth from the soil, create a sustaining and sustainable world for ourselves and for all that lives, and let us say ¡Que viva!

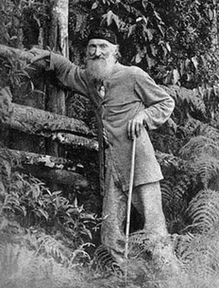

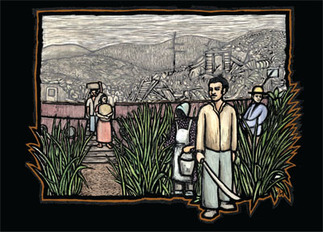

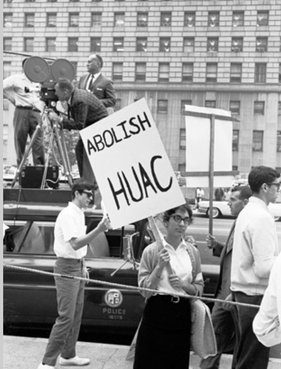

Fritz Muller Fritz Muller My hosts at the small cabin I found on airbnb, a friendly couple from Wisconsin, describe what surrounds their hand built, octagonal retreat as “jungle.” It’s a Hollywood word, full of Tarzanic imagery, an exoticizing word that conjures up fantasies of white colonial explorers cutting paths through the homelands of tropical people. I gently explain that this is not a jungle. It’s second growth subtropical forest, taking back land cleared over a century ago during the rise of the coffee kingdoms, a richly dense ecosystem, full of tree ferns and hanging vines, but not the primordial rainforest they imagine. Many of the tallest trees are imports, brought here to shade the coffee: red blossomed tulipán from West Africa, pomarosa and guamá from Venezuela. In the reclaiming of those cafetales, the monte, the wild, begins with yagrumos, shooting up from the million seeds each tree can produce, armed by its symbiosis with the little Azteca ants, who defend the saplings from insects and choking vines in exchange for shelter and the food provided by special glands yagrumo has evolved for the purpose, so called mullerian glands, named for pioneering German naturalist Fritz Müller, who, dismayed by the failed revolutions of 1848, went off to be a naturalist in Brazil.  Ausubo Trunk Ausubo Trunk Yagrumo always seems to me to be a talkative tree, waving its white palms in the air, announcing by flipping its palms back and forth like a child playing a tossing game, that the rain has begun to fall on the far slope, that a fresh breeze is blowing in from the Mona Passage, that the first edges an announced hurricane, the frothy skirts of Guabancex, her terrible winds and heavy downpours curving their way clockwise across the Caribbean, are approaching. Yagrumo is resilient. It bends its soft wood, and what breaks quickly regenerates. Not like the ancient hardwoods who take decades to reach maturity, ausubo, guayacán, capá blanco and capá prieto. (I say who because they are beings to me, family ancestors with stories to their names.)  San Ciriaco migrants in Hawai'i. www.rlmartstudio.com San Ciriaco migrants in Hawai'i. www.rlmartstudio.com After Hurricane Hugo, I was taken into the Luquillo rainforest by a biologist friend of my father’s. Whole hillsides looked like New England in November, leaves burnt brown by the salt wind, and ranks of tall mahoganies reduced to piles of splinters. This isn’t the disaster it seems to the uninitiated. The forests of my island evolved in a realm of storms, and ned the cleansing breaths of an occasional uprooting the way the western forests of North America need fire. But for the human inhabitants it’s another story. Don Luis, my best friend’s 97 year old father, still remembers finding a piece of zinc roofing impaling a large tree in a deep valley after the cataclysmic San Felipe hurricane of 1928. He and other elders have told me how when they crept out of their shelters it was to an unrecognizable landscape, stripped bare of all vegetation. In 1899, hurricane San Ciriaco left 100,000 homeless and starving. Don Luis’ father told him about the lines of silent, hungry people walking toward the coast, to “las emigraciones,” not knowing where in the world the ships were taking them except that it was away from eating leaves and mud. Over five thousand of them ended up in the cane fields of Hawaii and streets of San Francisco. I interviewed a remote cousin of Don Luis, a third generation Hawai’ian Puerto Rican whose family never returned.  Don Luis can name all of the dozens of hurricanes to strike the Western cordillera since then, and the near misses whose paths arced northward to the east or west of us, Hugo which tore pieces out of cement buildings on the island municipality of Vieques and left Indiera untouched, and Georges, which uprooted half the pines on our land and it was ten years, he tells me, before the mediopesos nested there again. I can imagine these slopes, a few years after San Felipe did its worst, greened over by the pioneering masses of fern and shrub and the graceful silhouettes of young yagrumos, hands raised to the sky, ants scurrying up and down the slender trunks, repelling the attempts of bejucos to get find a smothering foothold, spreading their shade for the delicate flowers of alegría to repopulate the scoured hills with color.  I vividly remember the day, in 1959, when my father was called up before the House Unamerican Activities Committee, during their hearings on the Puerto Rican left, of which he was a part. My parents had been blacklisted since 1951, when, on graduating from Cornell University, it was made clear to my father, a member of the Communist Party, that he would not find a job. Facing the possibility that he would be drafted into the army to fight in the newly erupted Korean War, my parents decided to go to Puerto Rico, unsure whether my father’s refusal to fight would result in jail time and separation. In Puerto Rico, a neighbor of my mother’s aunt pulled my father aside, told him she was part of a cell of the Nationalist Party, and that the FBI was visiting each place he applied for work, warning them not to hire him. On the advice of Alabama communist Jane Speed, who had moved to Puerto Rico in the late 1930s, they bought land, so they would at least have food to eat. In 1956 they moved back to New York so my father could attend graduate school at Columbia while my mother took classes at City College and parented me and my brother Ricardo. On the north side of the mountains, the overgrown side,where the trees have not been cut in at least 90 years, there are seven springs. One of them at least flows into the tiny Río Sapo and makes its way to the Caribbean sea. That northern slope, un-terraced, wild, always captured my imagination as a child. Living as we did on the very crest of the Cordillera Central, we could look down to the coast on three sides. Away to the north are the limestone karst hills near Arecibo, tiny carved and cave riddled hills resembling Chinese landscape paintings. When the rains came from that side, we could see its path as it struck the silver-lined leaves of yagrumo trees, flipping them so the undersides showed white, a wave of water walking across the far slope and the valley until the first drops began to strike the tin roof with a noise like hail. That uncultivated valley was full of lizard cuckoos, whose cries, like hoarse laughter, also seemed to come just before the rain.

Rain ruled our lives in so many ways, the presence of water and its absence. As humidity rises in the mountains, insects come out into the air and swallows and other birds begin swooping and diving to eat the, The little coquís in the underbrush sing more loudly, and the air itself seems to wake up and shout.  I’m in the highlands of Maricao, Puerto Rico, talking with my childhood best friend Carmen Ana Ríos and her 97 year old father. Don Luis tells me the land is exhausted, and doesn’t yield what it did. For a hundred and fifty years the mountains of Western Puerto Rico have produced some of the best coffee in the world, but now Coca Cola has bought up 60% of the island’s coffee companies, mixes it with cheap, lower quality beans from Mexico and Colombia and markets it as Puerto Rican, so the coffee itself isn’t what it was either. All along the roads are signs announcing once viable farms for sale, and tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds is buying, while the people of the mountains are being displaced, to Central Florida, Georgia, Texas. The coffee farms of my childhood were forest ecosystems, where tall shade trees kept the undergrowth to a minimum. As a boy, don Luis was sent up those trees once a year to open the canopy, so the sun could ripen the coffee. Before the harvest they’d clear the weeds once, then let the canopy close again, which controlled the weds without any further effort. Around thirty-five years ago the government began exerting pressure on farmers to cut down those forests and plant rows of sun grown Brazilian varieties that matured faster and yielded a little more. Without shade, the growers had to use herbicides to keep weeds under control. Without roots, the soil began to erode, washing downhill to silt the reservoir that provides this mountain community with water. There was no leaf litter to restore nutrients. Without trees, the birds declined. A rich tropical forest habitat became open hillsides with rows of low bushes. |

About Aurora

Aurora Levins Morales is a disabled and chronically ill, community supported writer, historian, artist and activist. It takes a village to keep her blogs coming. To become part of the village it takes, donate here. Never miss a post!

Click below to add this blog to your favorite RSS reader: Archives

September 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed